Ancient genome

from Africa

sequenced

for the first time

Africa, Anthropology, ArchaeoHeritage, Archaeology, Breakingnews, Ethiopia, Genetics

The first ancient human genome from Africa to be sequenced has revealed that a wave of migration back into Africa from Western Eurasia around 3,000 years ago was up to twice as significant as previously thought, and affected the genetic make-up of populations across the entire African continent. The Mota cave is located in a mountainous region, and its entrance is about 6,000 feet above sea level.

Weather and the changing conditions of the only road that runs near the cave -- a gravel surface -- made access complicated for the research team

[Credit: Kathryn and John Arthur]

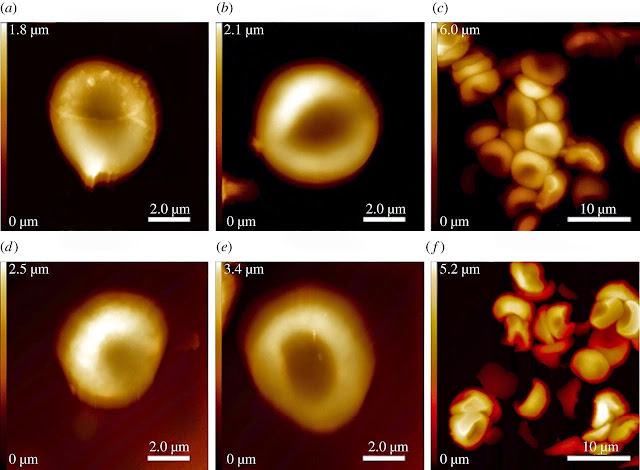

The genome was taken from the skull of a man buried face-down 4,500 years ago in a cave called Mota in the highlands of Ethiopia -- a cave cool and dry enough to preserve his DNA for thousands of years. Previously, ancient genome analysis has been limited to samples from northern and arctic regions. The latest study is the first time an ancient human genome has been recovered and sequenced from Africa, the source of all human genetic diversity. The findings are published in the journal Science. The ancient genome predates a mysterious migratory event which occurred roughly 3,000 years ago, known as the 'Eurasian backflow', when people from regions of Western Eurasia such as the Near East and Anatolia suddenly flooded back into the Horn of Africa.

Entrance to the Mota Cave in the Ethiopian highlands

[Credit: Kathryn and John Arthur]

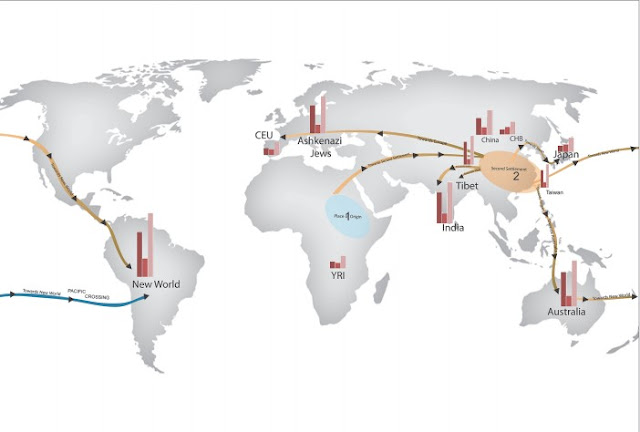

The genome enabled researchers to run a millennia-spanning genetic comparison and determine that these Western Eurasians were closely related to the Early Neolithic farmers who had brought agriculture to Europe 4,000 years earlier. By comparing the ancient genome to DNA from modern Africans, the team have been able to show that not only do East African populations today have as much as 25% Eurasian ancestry from this event, but that African populations in all corners of the continent -- from the far West to the South -- have at least 5% of their genome traceable to the Eurasian migration. Researchers describe the findings as evidence that the 'backflow' event was of far greater size and influence than previously thought. The massive wave of migration was perhaps equivalent to over a quarter of the then population of the Horn of Africa, which hit the area and then dispersed genetically across the whole continent.

The view looking out from the Mota cave in the Ethiopian highlands, where the remains containing the ancient genome were found

[Credit: Kathryn and John Arthur]

"Roughly speaking, the wave of West Eurasian migration back into the Horn of Africa could have been as much as 30% of the population that already lived there -- and that, to me, is mind-blowing. The question is: what got them moving all of a sudden?" said Dr Andrea Manica, senior author of the study from the University of Cambridge's Department of Zoology. Previous work on ancient genetics in Africa had involved trying to work back through the genomes of current populations, attempting to eliminate modern influences. "With an ancient genome, we have a direct window into the distant past. One genome from one individual can provide a picture of an entire population," said Manica. The cause of the West Eurasian migration back into Africa is currently a mystery, with no obvious climatic reasons. Archaeological evidence does, however, show the migration coincided with the arrival of Near Eastern crops into East Africa such as wheat and barley, suggesting the migrants helped develop new forms of agriculture in the region.

In Mota cave, located in the Gamo highlands of Ethiopia, a group of NSF-supported researchers excavation a rock cairn. They discovered under it a burial site containing the remains of a 4,500-year skeleton

[Credit: Kathryn and John Arthur]

The researchers say it's clear that the Eurasian migrants were direct descendants of, or a very close population to, the Neolithic farmers that had had brought agriculture from the Near East into West Eurasia around 7,000 years ago, and then migrated into the Horn of Africa some 4,000 years later. "It's quite remarkable that genetically-speaking this is the same population that left the Near East several millennia previously," said Eppie Jones, a geneticist at Trinity College Dublin who led the laboratory work to sequence the genome. While the genetic make-up of the Near East has changed completely over the last few thousand years, the closest modern equivalents to these Neolithic migrants are Sardinians, probably because Sardinia is an isolated island, says Jones. "The famers found their way to Sardinia and created a bit of a time capsule. Sardinian ancestry is closest to the ancient Near East." "Genomes from this migration seeped right across the continent, way beyond East Africa, from the Yoruba on the western coast to the Mbuti in the heart of the Congo -- who show as much as 7% and 6% of their genomes respectively to be West Eurasian," said Marcos Gallego Llorente, first author of the study, also from Cambridge's Zoology Department.

John Arthur, an NSF-supported archaeologist at the University of South Florida St. Petersburg, excavates the Mota cave site

[Credit: Kathryn and John Arthur]

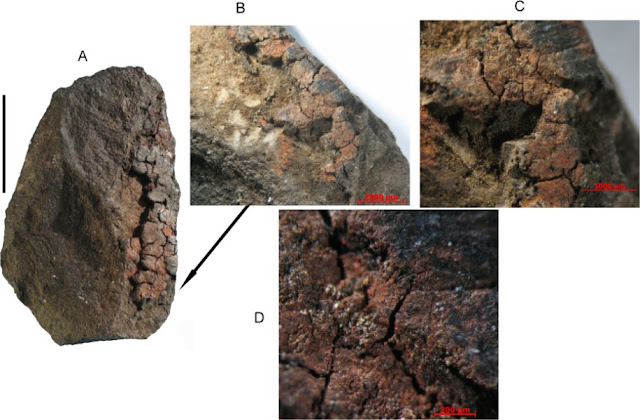

"Africa is a total melting pot. We know that the last 3,000 years saw a complete scrambling of population genetics in Africa. So being able to get a snapshot from before these migration events occurred is a big step," Gallego Llorente said. The ancient Mota genome allows researchers to jump to before another major African migration: the Bantu expansion, when speakers of an early Bantu language flowed out of West Africa and into central and southern areas around 3,000 years ago. Manica says the Bantu expansion may well have helped carry the Eurasian genomes to the continent's furthest corners. The researchers also identified genetic adaptations for living at altitude, and a lack of genes for lactose tolerance -- all genetic traits shared by the current populations of the Ethiopian highlands. In fact, the researchers found that modern inhabitants of the area highlands are direct descendants of the Mota man. Finding high-quality ancient DNA involves a lot of luck, says Dr Ron Pinhasi, co-senior author from University College Dublin. "It's hard to get your hands on remains that have been suitably preserved. The denser the bone, the more likely you are to find DNA that's been protected from degradation, so teeth are often used, but we found an even better bone -- the petrous." The petrous bone is a thick part of the temporal bone at the base of the skull, just behind the ear. "The sequencing of ancient genomes is still so new, and it's changing the way we reconstruct human origins," added Manica. "These new techniques will keep evolving, enabling us to gain an ever-clearer understanding of who our earliest ancestors were." The study was conducted by an international team of researchers, with permission from the Ethiopia's Ministry of Culture and Authority for Research and Conservation of Cultural Heritage.

Source: University of Cambridge [October 08, 2015]