Una curiosità interessante: le differenze aggregative sociali tra Nord e Sud della Cina riproducono quelle più grandi esistenti fra Cina e Mondo Occidentale.

Sembra che ciò dipenda - secondo questo studio psicologico antropologico - da differenti arttitudini indotte dal coltivare grano (nord della Cina) e coltivare riso (coltura tradizionale del sud della Cina).

Il primo tipo di coltura renderebbe gli uomini più orientato verso l'aggregazione in comunità, mentre il secondo tipo condurrebbe a maggiore individualismo.

"Rice theory" in China.

A new cultural psychology study has found that psychological differences

between the people of northern and southern China mirror the

differences between community-oriented East Asia and the more

individualistic Western world -- and the differences seem to have come

about because southern China has grown rice for thousands of years,

whereas the north has grown wheat.

'Rice theory' explains north-south China cultural differences

A new cultural psychology study has found that psychological differences

between the people

of northern and southern China mirror the differences between

community-oriented East Asia

and the more individualistic Western world -- and the differences seem

to have come

about because southern China has grown rice for thousands of years,

whereas the north

has grown wheat [Credit: Handout/Getty Images]

"It's easy to think of China as a single culture, but we found that

China has very distinct northern and southern psychological cultures and

that southern China's history of rice farming can explain why people in

southern China are more interdependent than people in the wheat-growing

north," said Thomas Talhelm, a University of Virginia Ph.D. student in

cultural psychology and the study's lead author. He calls it the "rice

theory." The findings appear in the May 9 issue of the journal Science.

Talhelm and his co-authors at universities in China and Michigan propose

that the methods of cooperative rice farming -- common to southern

China for generations -- make the culture in that region interdependent,

while people in the wheat-growing north are more individualistic, a

reflection of the independent form of farming practiced there over

hundreds of years.

"The data suggests that legacies of farming are continuing to affect

people in the modern world," Talhelm said. "It has resulted in two

distinct cultural psychologies that mirror the differences between East

Asia and the West."

According to Talhelm, Chinese people have long been aware of cultural

differences between the north region and the southern, which are divided

by the Yangtze River -- the largest river in China, flowing west to

east across the vast country. People in the north are thought to be more

aggressive and independent, while people to the south are considered

more cooperative and interdependent.

"This has sometimes been attributed to different climates -- warmer in

the south, colder in the north -- which certainly affects agriculture,

but it appears to be more related to what Chinese people have been

growing for thousands of years," Talhelm said.

He notes that rice farming is extremely labor-intensive, requiring about

twice the number of hours from planting to harvest as does wheat. And

because most rice is grown on irrigated land, requiring the sharing of

water and the building of dikes and canals that constantly require

maintenance, rice farmers must work together to develop and maintain an

infrastructure upon which all depend. This, Talhelm argues, has led to

the interdependent culture in the southern region.

Wheat, on the other hand, is grown on dry land, relying on rain for

moisture. Farmers are able to depend more on themselves, leading to more

of an independent mindset that permeates northern Chinese culture.

Talhelm developed his rice theory after living in China for four years.

He first went to the country in 2007 as a high school English teacher in

Guangzhou, in the rice-growing south.

A year later, he moved to Beijing, in the north. On his first trip

there, he noticed that people were more outgoing and individualistic

than in the south.

"I noticed it first when a museum curator told me my Chinese was clearly

better than my roommate's," Talhelm said. "The curator was being direct

and a little less concerned about how her statement might make us

feel."

After three years in China, including time as a journalist, he later

went back as a U.Va. doctoral student on a Fulbright scholarship.

"I was pretty sure the differences I was seeing were real, but I had no

idea why northern and southern China were so different -- where did

these differences come from?" Talhelm asked.

He soon found that the Yangtze was an important cultural divider in

China. "I found out that the Yangtze River helped divide dialects in

China, and I soon learned that the Yangtze also roughly divides rice

farming and wheat farming," he said.

He dug into anthropologists' accounts of pre-modern rice and wheat

villages and realized that they might account for the different

mindsets, carried forward from an agrarian past into modernity.

"The idea is that rice provides economic incentives to cooperate, and

over many generations, those cultures become more interdependent,

whereas societies that do not have to depend on each other as much have

the freedom of individualism," Talhelm said. He went about investigating

this with his Chinese colleagues by conducting psychological studies of

the thought styles of 1,162 Han Chinese college students in the north

and south and in counties at the borders of the rice-wheat divide.

They found through a series of tests that northern Chinese were indeed

more individualistic and analytic-thinking -- more similar to Westerners

-- while southerners were interdependent, holistic-thinking and

fiercely loyal to friends, as psychological testing has shown is common

in other rice-growing East Asian nations, such as Japan and Korea.

The study was conducted in six Chinese cities: Beijing in the north;

Fujian in the southeast; Guangdong in the south; Yunnan in the

southwest; Sichuan in the west central; and Liaoning in the northeast.

Talhelm said that one of the most striking findings was that counties on

the north-south border -- just across the Yangtze River from each other

-- exhibited the same north/south psychological characteristics as

areas much more distantly separated north and south. "I think the rice

theory provides some insight to why the rice-growing regions of East

Asia are less individualistic than the Western world or northern China,

even with their wealth and modernization," Talhelm said.

He expects to complete his Ph.D. next year, and this year received an

Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences Research Fellowship from U.Va.'s

Office of the Vice President for Research and the Graduate School of

Arts & Sciences for an in-depth study of people from the rice-wheat

border in China's Anhui province.

Source: University of Virginia [May 08, 2014]

Read more at: http://archaeologynewsnetwork.blogspot.it/2014/05/rice-theory-explains-north-south-china.html?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed:+TheArchaeologyNewsNetwork+(The+Archaeology+News+Network)#.U3Ge0nYarpc

Follow us: @ArchaeoNewsNet on Twitter | groups/thearchaeologynewsnetwork/ on Facebook

L'uomo percepisce l'ambiente attraverso i cinque sensi. Inoltre, possiede una percezione particolare - che è quella del tempo - che non è solamente un adattamento automatico al clima, all'irradiazione solare ed alla stagione (come in alcuni altri animali) bensì è la capacità critica di percepire il trascorrere del proprio tempo biologico, nell'ambiente.Di tutto questo vorrei parlare, per i primi 150 anni: poi, forse patteggeremo su quale prossimo argomento discorrere insieme

Visualizzazione post con etichetta Psicologia. Mostra tutti i post

Visualizzazione post con etichetta Psicologia. Mostra tutti i post

martedì 13 maggio 2014

lunedì 23 settembre 2013

Perché il linguaggio è unicamente umano?

Why is language unique to humans?

New research published today in Journal of the Royal Society Interface suggests that human language was made possible by the evolution of particular psychological abilities.

Researchers from Durham University explain that the uniquely expressive power of human language requires humans to create and use signals in a flexible way. They claim that his was only made possible by the evolution of particular psychological abilities, and thus explain why language is unique to humans.

Using a mathematical model, Dr Thomas Scott-Phillips and his colleagues, show that the evolution of combinatorial signals, in which two or more signals are combined together, and which is crucial to the expressive power of human language, is in general very unlikely to occur, unless a species has some particular psychological mechanisms. Humans, and probably no other species, have these, and this may explain why only humans have language.

In a combinatorial communication system, some signals consist of the combinations of other signals. Such systems are more efficient than equivalent, non-combinatorial systems, yet despite this they are rare in nature. Previous studies have not sufficiently explained why this is the case. The new model shows that the interdependence of signals and responses places significant constraints on the historical pathways by which combinatorial signals might emerge, to the extent that anything other than the most simple form of combinatorial communication is extremely unlikely.

The scientists argue that these constraints can only be bypassed if individuals have the sufficient socio-cognitive capacity to engage in ostensive communication. Humans, but probably no other species, have this ability. This may explain why language, which is massively combinatorial, is such an extreme exception to nature’s general trend.

Authors: Thomas C. Scott-Phillips and Richard A. Blythe | Source: The Royal Society [September 18, 2013]

|

| A mural in Teotihuacan, Mexico (ca. 200 AD) depicting a person emitting a speech scroll from his mouth, symbolizing speech [Credit: Daniel Lobo/WikiCommonjs] |

Using a mathematical model, Dr Thomas Scott-Phillips and his colleagues, show that the evolution of combinatorial signals, in which two or more signals are combined together, and which is crucial to the expressive power of human language, is in general very unlikely to occur, unless a species has some particular psychological mechanisms. Humans, and probably no other species, have these, and this may explain why only humans have language.

In a combinatorial communication system, some signals consist of the combinations of other signals. Such systems are more efficient than equivalent, non-combinatorial systems, yet despite this they are rare in nature. Previous studies have not sufficiently explained why this is the case. The new model shows that the interdependence of signals and responses places significant constraints on the historical pathways by which combinatorial signals might emerge, to the extent that anything other than the most simple form of combinatorial communication is extremely unlikely.

The scientists argue that these constraints can only be bypassed if individuals have the sufficient socio-cognitive capacity to engage in ostensive communication. Humans, but probably no other species, have this ability. This may explain why language, which is massively combinatorial, is such an extreme exception to nature’s general trend.

Authors: Thomas C. Scott-Phillips and Richard A. Blythe | Source: The Royal Society [September 18, 2013]

mercoledì 4 settembre 2013

Linguaggio & fabbricazione di utensili

Language and tool-making skills evolved at same time

Lo stato della ricerca , presso l'Università di Liverpool porta a concludere che il cervello sfrutta le medesime capacità per il linguaggio e per la costruzione di utensili: pertanto le due capacità umane potrebbero essersi evolute contemporaneamente.

Research by the University of Liverpool has found that the same brain activity is used for language production and making complex tools, supporting the theory that they evolved at the same time.

I ricercatori dell'Università hanno controllato l'attività cerebrale di 10 esperti lavoratori della pietra (scheggiatori) sia mentre producevano un utensile, sia mentre affrontavano un test del linguaggio.

|

| Three hand axes produced by participants in the experiment. Front, back and side views are shown [Credit: University of Liverpool] |

Researchers from the University tested the brain activity of 10 expert stone tool makers (flint knappers) as they undertook a stone tool-making task and a standard language test.

Misurato il flusso ematico durante l'attività.

Misurato il flusso ematico durante l'attività.

Brain blood flow activity measured

E' stato misurato il flusso ematico cerebrale dei partecipanti, durante ambedue le attività, usando un ecodoppler grafia funzionale transcranica, che normalmente si impiega per valutare l'eventuale danno cerebrale post traumatico o pre operatorio.

E' stato misurato il flusso ematico cerebrale dei partecipanti, durante ambedue le attività, usando un ecodoppler grafia funzionale transcranica, che normalmente si impiega per valutare l'eventuale danno cerebrale post traumatico o pre operatorio.

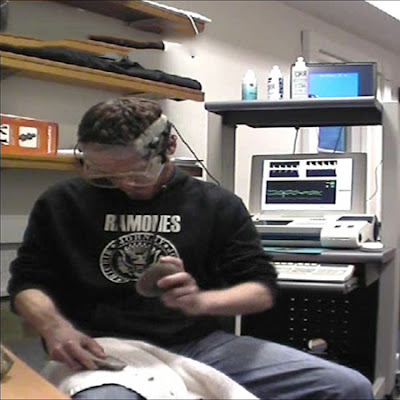

They measured the brain blood flow activity of the participants as they performed both tasks using functional Transcranial Doppler Ultrasound (fTCD), commonly used in clinical settings to test patients’ language functions after brain damage or before surgery.

I ricercatori hanno ottenuto pattern cerebrali correlati per ambedue le attività, il che suggerisce che ambedue sfruttano le medesime aree cerebrali. Il linguaggio e la capacità di produrre utensili di forma voluta dalle pietre sono attività considerate caratteristiche esclusivamente umane, che hanno avuto un'evoluzione di milioni di anni.

I ricercatori hanno ottenuto pattern cerebrali correlati per ambedue le attività, il che suggerisce che ambedue sfruttano le medesime aree cerebrali. Il linguaggio e la capacità di produrre utensili di forma voluta dalle pietre sono attività considerate caratteristiche esclusivamente umane, che hanno avuto un'evoluzione di milioni di anni.

The researchers found that brain patterns for both tasks correlated, suggesting that they both use the same area of the brain. Language and stone tool-making are considered to be unique features of humankind that evolved over millions of years.

Darwin fu il primo a suggerire che l'uso di strumenti ed il linguaggio potessero essere andati incontro ad un'evoluzione contemporanea, in quanto entrambe le capacità dipendono da una complessa pianificazione e dalla coordinazione di differenti azioni, ma fino ad oggi non si era data una prova convincente di questa possibilità.

|

| The brain activity of an experienced flint-knapper is monitored using a Transcranial Doppler Ultrasound, as he works the stone [Credit: University of Liverpool] |

Darwin was the first to suggest that tool-use and language may have co-evolved, because they both depend on complex planning and the coordination of actions but until now there has been little evidence to support this.

Il dottor Georg Meyer, del Dipartimento di psicologia Sperimentale sostiene "Questo è il primo studio sul cervello che metta direttamente a confronto la confezione di manufatti complessi ed il linguaggio".

Il dottor Georg Meyer, del Dipartimento di psicologia Sperimentale sostiene "Questo è il primo studio sul cervello che metta direttamente a confronto la confezione di manufatti complessi ed il linguaggio".

Dr Georg Meyer, from the University Department of Experimental Psychology, said: “This is the first study of the brain to compare complex stone tool-making directly with language.

La manifattura di strumenti ed il linguaggio evolvettero parallelamente.

La manifattura di strumenti ed il linguaggio evolvettero parallelamente.

Tool use and language co-evolved

"Il nostro studio ha correlato i pattern del flusso ematico nei primi 10 secondi dall'inizio del compito, in ambedue le attività. Questo dimostra che ambedue le attività sono dipendenti dalle stesse aree cerebrali ed è coerente con la teoria per cui la costruzione di strumenti complessi di pietra ed il linguaggio si evolvettero contemporaneamente e condividono analoghi percorsi nel cervello".

"Il nostro studio ha correlato i pattern del flusso ematico nei primi 10 secondi dall'inizio del compito, in ambedue le attività. Questo dimostra che ambedue le attività sono dipendenti dalle stesse aree cerebrali ed è coerente con la teoria per cui la costruzione di strumenti complessi di pietra ed il linguaggio si evolvettero contemporaneamente e condividono analoghi percorsi nel cervello".

“Our study found correlated blood-flow patterns in the first 10 seconds of undertaking both tasks. This suggests that both tasks depend on common brain areas and is consistent with theories that tool-use and language co-evolved and share common processing networks in the brain.”

La dott.sa Natalie Uomini del Dipartimento di archeologia (Classics & Egiptology) conferma che nessuno prima aveva misurato l'attività cerebrale mentre il soggetto costruiva uno strumento: si tratta di una prima volta, sia per la psicologia, sia per l'archeologia.

La dott.sa Natalie Uomini del Dipartimento di archeologia (Classics & Egiptology) conferma che nessuno prima aveva misurato l'attività cerebrale mentre il soggetto costruiva uno strumento: si tratta di una prima volta, sia per la psicologia, sia per l'archeologia.

Dr Natalie Uomini from the University’s Department of Archaeology, Classics & Egyptology, said: “Nobody has been able to measure brain activity in real time while making a stone tool. This is a first for both archaeology and psychology.”

I risultati sono pubblicati su PLoS ONE.

I risultati sono pubblicati su PLoS ONE.

Source: University of Liverpool [September 02, 2013]

Iscriviti a:

Post (Atom)