Fu noto come "Coso Artifact".

Si tratta di un ‘oopart’ (sigla inglese per: out of place artifact, artefatto fuori posto) ed è un caso

esemplare.

- Che cos’é.

Si tratta di una candela d'accensione per automobile, incastonata in roccia o argilla compressa, rinvenuta il 13 di febbraio

del 1961 da tre persone che cercavano geodi, in California.

- Come avvenne.

Quello che ai tre sembrò un geode qualunque, fu regolarmente

raccolto e portato a casa, dove fu come al solito tagliato a metà (sacrificando

un’intera lama rotante diamantata nuova), per rivelare non l’aspetto cavo comune a tutti i

geodi, bensì quello che sembrava un’incredibile anomalia scientifica e storica:

all’interno, invece della solita cavità, si trovava materiale compatto bianco,

|

| le due facce di sezione del Coso Artifact. |

somigliante a durissima porcellana, includente metallo brillante chiaro,

magnetizzato, dello spessore di due millimetri. Intorno alla porcellana c’era

uno strato di rame corroso e ancora all’esterno uno strato di minerale di

sezione esagonale. Tutto intorno si trovavano conchiglie fossili e due oggetti

metallici non magnetici che sembravano un chiodo ed una rondella.

|

| L'aspetto esterno. |

Subito si sparse la voce che si era trovata una candela (un prodotto artificiale: mai prodotto dall’uomo

prima del XIX secolo) naturalmente incastonata in un geode, che fu riferito essere stato valutato da un

esperto geologo come risalente a 500.000 anni prima.

- Dove avvenne.

Il ritrovamente fu effettuato dai tre a nove chilometri (6

miglia) a nord est di Olancha, presso una cima di 1300 metri (4.300 piedi).

Va detto che – all’epoca – non esistevano mezzi sicuri di

datazione (includendo l’uso di fossili guida) e che il ‘geologo esperto’ che

aveva offerto la propria valutazione non fu mai reperito, né mai comparve una

pubblicazione scientifica in questo senso.

Oggi la geologia riconosce sperimentalmente che i noduli presenti intorno

all’artefatto possono formarsi nell’arco

anni o decadi, quindi in tempi compatibili con il ritrovamento di comune

immondizia scartata perché inutile.

- Gli effetti pseudoscientifici.

Nacquero presto le varie ipotesi fantasiose speculative (non indovini quali?):

1)

Atlantide, naturalmente, non manca mai in questo genere di cose.

2)

I visitatori extraterrestri, che ci sono tanto cari, ormai.

3)

I viaggiatori nel tempo dal futuro, che sbadatamente perdono

alcuni oggetti, durante una visita nel passato.

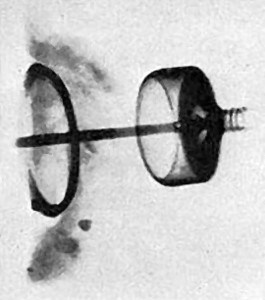

|

| l'aspetto radiografico del "Coso Artefact" |

- Lo studio.

L’oggetto fu radiografato. Furono identificate la marca e

l’anno di produzione (per la cronaca: Champion, 1920) e la destinazione

(automobile Ford, modelli T ed A). Di conseguenza è poco credibile che si

trovasse in un posto isolato e lontano da una strada percorribile da un’auto.

Gli oggetti contenenti ferro rapidamente si arrugginiscono nel

suolo, formando rapidamente intorno a sé concrezioni di ossido di ferro.

L’oggetto non era un geode, solitamente cavo e composto di silice calcedonica

all’esterno e di eleganti cristalli di quarzo all’interno. La sua durezza (3

nella scala di durezza di Mohs) era molto inferiore a quella usuale di un geode.

- Il seguito.

Fu fatto un tentativo di vendita dell’oggetto, per 25.000

dollari.

W. Lane, che ne risulta essere stato l’ultimo proprietario

conosciuto, è deceduto.

A tutt’oggi, dei tre cercatori, uno è morto, uno è vivente

ma si rifiuta di rilasciare dichiarazioni, il terzo è introvabile.

La localizzazione precisa del ritrovamento è quindi oggi

impossibile, guarda caso.

|

| Un reperto nuovo, a futura memoria ed imperituro monito |

- Conclusione.

Come si vede bene, sono presenti qui proprio tutti gli

elementi classici utili a riconoscere la presenza del falso e dei falsari: in

questo caso è più facile, certamente, in quanto è stato congegnato (volutamente

o per caso) da gente semplice. In altri casi, invece, ci si trova di fronte a

falsi eruditi (ad esempio, quelli epigrafici o archeologici): quelli richiedono molta maggiore attenzione, l’intervento di veri esperti

della materia e in ultimo – ove necessario – l’intervento del tribunale, civile o penale.

Ma la considerazione finale è – e deve essere – sempre la

medesima: colui che sostiene l’autenticità di oggetti e concetti dimostrati con

certezza falsi o è in grave errore, oppure è anch’egli un falsario.

La scelta è obbligata – pertanto – tra l’essere un cretino riconosciuto, oppure un colpevole

complice del falso.

Per chi desiderasse la versione Inglese di due degli studiosi VERI che si sono dedicati all'esame del "Coso Artifact", ecco lo qui di seguito, con riferimenti bibliografici, non senza l'aggiunta di una mia nota di biasimo per la necessità di perdere tempo prezioso dietro alla caccia dell'oca selvaggia (wild goose hunt) per colpa di colpevoli imbecilli:

The story of the Coso Artifact has been embellished over the years, but nearly all accounts of the actual discovery are basically the same. On February 13, 1961, Wallace Lane, Virginia Maxey, and Mike Mikesell were seeking interesting mineral specimens, particularly geodes, for their LM&V Rockhounds Gem and Gift Shop in Olancha, California. The trio was about 6 miles northeast of Olancha, near the top of a peak about 4300 feet in elevation and about 340 feet above the dry bed of Owens Lake. At lunchtime, after collecting rocks most of the morning, all three placed their specimens in the rock sack Mikesell was carrying (Steiger 1974: 49).

The next day in the gift shop's workroom, Mikesell ruined a nearly new diamond saw blade while cutting what he thought was a geode. Inside the cut nodule, Mikesell did not find the cavity that is typical of geodes, but a perfectly circular section of very hard, white material that appeared to be porcelain. In the center of the porcelain cylinder was a 2-millimeter shaft of bright metal. The metal shaft responded to a magnet. There were other odd qualities about the specimen. The outer layer of the specimen was encrusted with fossil shells and their fragments. In addition to shells, the discoverers noticed two nonmagnetic metallic objects in the crust, resembling a nail and a washer. Stranger still, the inner layer was hexagonal and seemed to form a casing around the hard porcelain cylinder. Within the inner layer, a layer of decomposing copper surrounded the porcelain cylinder.

The last individual known to possess the Coso Artifact was one of the original discoverers, Wallace Lane. Lane had the object on display in his home, but he adamantly refused to allow anyone to examine it (Willis 1969). However, he had a standing offer to sell it for $25 000. In September 1999, a national search to locate any of the original discoverers proved fruitless. We suspect that Lane is dead. Maxey is alive, but is avoiding any public comment, and the whereabouts of Mikesell remain unknown. The location and disposition of the artifact are also unknown. Willis's 1969 article is the primary source for information on this object to date.

INFO Journal editor Willis speculated that the artifact was some sort of spark plug. His brother found the suggestion extraordinary: "I was thunderstruck," he wrote, "for suddenly all the parts seemed to fit. The object sliced in two shows a hexagonal part, a porcelain or ceramic insulator with a central metallic shaft - the basic components of any spark plug" (Willis 1969). However, they could not reconcile the upper end featuring a "spring", "helix", or "metal threads" with any contemporary spark plug. So the mystery continued. The artifact even appeared briefly at the end of an In Search Of ... episode hosted by Leonard Nimoy.

The internet offers a plethora of other opinions on the subject. While most writers simply report the mystery as described earlier, some have taken to speculating on the purpose and origin of such a device. Brian Wood, describing himself as "Co-Producer, ParaNet UFO Continuum [and] International Director of MICAP [Multinational Investigations Cooperative on Aerial Phenomena]", suggested that if it is not simply a spark plug, "My guess would be some sort of antenna. The construction reminds me of modern attempts at superconductors" (Wood 1999).

Joe Held of "Joe's UFOs and Space Mysteries" thinks that the device "looks similar to a small capacitor with several different materials. The object is roughly the size of an auto spark plug. Since the formation of geodes can take millions of years this was a very curious find indeed" (Held 1999).

Elsewhere in the Pacific Northwest, Institute for Creation Research (ICR) adjunct faculty member Donald Chittick has been heavily promoting the Coso Artifact. In The Puzzle of Ancient Man, Chittick (1997) presents the Coso Artifact as evidence that ancient civilizations were extremely advanced. Presuming that it is an ancient spark plug, Chittick explains his inference that this find indicates technological sophistication. He admits that reliable dates are unlikely, but then goes on to argue that the plug is old because geodes take too long to form. Chittick's discussion assumes that the plug was found inside a naturally occurring geode, which would indicate great age and therefore an "out-of-place" artifact. This, he argues, refutes evolution, since evolutionary models fail to explain the existence of such sophisticated technology so long ago.

Geodes consist of a thin outer shell composed of dense chalcedonic silica and filled with a layer of quartz crystals. The Coso Artifact does not possess either feature. Maxey referred to the material covering the artifact as "hardened clay" and noted that it had picked up a miscellaneous collection of pebbles, including a "nail and washer". Analysis of the surface material using the standard Mohs scale suggests a hardness of Mohs 3, which is much softer than chalcedony.

Other arguments regarding the ancient source of the Coso Artifact focus on the alleged fossil shells encrusted on the surface. If, as noted earlier, a nail and washer were also found on the same surface as the fossil shells, then the power of the inference of an ancient age for the artifact is seriously diminished. Even creationist literature notes how transport, erosion, or other geological changes in surface materials can lead to mistaken assumptions about the true age of individual objects. For example, Creation Ex Nihilo's June-August 1998 issue features fence wire that had become encased by surface materials including "fossil" seashells ([Anonymous] 1998b, quotation marks in the original; see also [Anonymous] 1991, 1998a, 1999).

A clue to what is revealed in the X-ray lies in one of the earliest articles about the artifact. Willis (1969) suggested that the upper end of the object "is actually the remains of a corroded piece of metal with threads." The Willis brothers seriously suspected the object was a contemporary spark plug, but were still unable to explain what was in the X-ray. Spark plugs of the 1960s typically terminated with no visible threading and tapered to a dull point. Though many of the interested parties agreed that the artifact bore a striking resemblance to a 20th-century spark plug, no one seems to have considered the idea of evolution - specifically, spark plug evolution.

Investigating the origins of the Coso Artifact revealed that mining operations were conducted in the area of discovery early in the 20th century. If internal combustion engines were used in these operations in the Coso mountain range, they would have been a very new technology at the time. So we extrapolated that spark plug technology would also have been in its infancy. To help us to learn more about spark-plug technology of a century ago, we enlisted the help of the Spark Plug Collectors of America (SPCA). We sent letters to four different spark plug collectors describing the Coso Artifact, including Calais's X-rays of the object in question. We expected the SPCA to provide some vague hints or no information at all about the artifact. The actual answers were stunning.

On September 9, 1999, Chad Windham, President of the SPCA, called Pierre Stromberg. Windham initially suspected that Stromberg was a fellow spark plug collector, writing incognito, with the motive of hoaxing him. His fears were compounded by the fact that there is an actual line of spark plugs named "Stromberg". Though Stromberg repeatedly assured Windham that his intentions were purely for research, he was puzzled why Windham was so suspicious and asked him to explain. Windham replied that it was so obvious to him that the artifact was a contemporary spark plug, the letter had to be a hoax. "I knew what it was the moment I saw the X-rays," Windham wrote.

Stromberg asked Windham if he could identify the particular make of the spark plug. Windham replied he was certain that it was a 1920s-era Champion spark plug. Later, Windham sent 2 identical spark plugs for comparison. Ten days after Windham's telephone call, Bill Bond, founder of the SPCA and curator of a private museum of spark plugs containing more than 2000 specimens, called Stromberg. Bond said he thought he knew the identity of the Coso Artifact: "A 1920s Champion spark plug." Spark plug collectors Mike Healy and Jeff Bartheld (Vice President of the SPCA) also concurred with Bond's and Windham's assessment about the spark plug. To date, there has been no dissent among the spark plug collectors as to the identity of the Coso Artifact.

Since Windham mentioned that spark plug collectors enjoy pulling pranks on one another, the question of deliberate fraud inevitably crops up in relation to the Coso Artifact. However, there is little hard evidence that the original discoverers intended to deceive anyone from the start. Furthermore, the Spark Plug Collectors of America was formed in 1975, well after the discovery of the artifact, and none of the 3 discoverers was ever affiliated with the organization.

Proponents of fantastic stories regarding the artifact have made mention of mysterious copper rings that encase the porcelain. But this too can be easily explained. Windham provided one completely disassembled plug (specimen #1). It revealed a pair of copper rings sandwiching an asbestos lining. According to Windham, this design was necessary because porcelain and steel have vastly differing expansion rates, so the copper was used to compensate for some of the problems this difference caused.

Specimen #2 was not disassembled by Windham, but also presented a feature that could explain why the artifact had not been identified decades ago. Specimen #2, though suffering from severe tarnish, came with a top nut screwed into its top hat. Almost all Champion spark plug advertisements of the first half of the 20th century showed pictures of their spark plugs including the top nut already screwed into place. In some cases, the top nut comes in two forms, one of which closely mimics the tip of today's contemporary spark plugs, which have no threading whatsoever. So it becomes rather easy to understand why the appearance of threads in the Coso Artifact seemed so puzzling to the original investigators.

It should be noted that the corrosion of the Coso Artifact almost completely destroyed any of the iron-alloy-based components, with the exception of the metal shaft encased in the porcelain cylinder. The samples received from Windham also revealed corrosion of the iron-based components, but the brass top hats were unscathed, except for some tarnishing. If the Coso Artifact is indeed a 1920s-era Champion spark plug, the X-ray of an almost perfectly preserved top hat is exactly what one would expect. Brass, a copper-zinc alloy, is commonly engineered to resist corrosion far better than iron-based alloys. In harsh environments, copper tends to outlast iron, but still succumbs fairly quickly. The rates of decay in the Coso Artifact match the rates of decay one would see in a 1920s-era Champion spark plug. An excellent review (Cronyn 1990) of how ferrous and non-ferrous alloys decay over time includes numerous photographs, including X-rays, of contemporary objects that have completely decayed into oxide nodules. Like the Coso Artifact, these examples also feature empty cavities where the original materials once resided.

The formation of the iron oxide nodule probably was hastened by the fact that corrosive "mineral dust" is blown off the dry lake bed of Lake Owen and onto the surrounding uplands where the artifact was discovered. This dust contains salts created by the evaporation of the lake water that are regularly blown off the lake bed by local windstorms. The US Geological Survey has conducted extensive investigations of this phenomena (Reheis 1997).

Once the investigation revealed beyond a reasonable doubt the true nature of the artifact, Stromberg notified Chittick via postal mail, warning him about the publication of this paper and urging him to issue a retraction and to paste a disclaimer in his book that the Coso Artifact story is fallacious. Chittick never responded, and the second edition of The Puzzle of Ancient Man promotes the Artifact with no disclaimer, but Chittick seems to have stopped mentioning the artifact in his public lectures. When Ken Clark of Spokane's Creation Outreach learned that the Artifact was a 1920s-era Champion spark plug and was offered detailed proof, he ceased to communicate with us. Although Creation Outreach continues to promote the spark plug on its web site by reproducing Jochmans (1979), it adds the editorial note: "Several readers have stated the artifact is indeed a sparkplug from the 1920s" (see http://home.att.net/~creationoutreach/pages/strange.htm).

The Coso Artifact was indeed a remarkable device. It was a 1920s-era Champion spark plug that probably powered a Ford engine, possibly modified to serve mining operations in the Coso mountain range of California. To suggest that it was a device belonging to an advanced civilization of the ancient past could be interpreted as true, but only if we redefine "ancient" to mean "the early 20th century".

Anonymous. 1998a. Bell-ieve It: Rapid rock formation rings true. Creation Ex Nihilo 20 (2): 6.

Anonymous. 1998b. Fascinating fossil fence-wire. Creation Ex Nihilo 20 (3): 6.

Anonymous. 1999. Sparking interest in rapid rocks. Creation Ex Nihilo 21 (4): 6.

Baugh CE. 1989. Academic justification for voluntary inclusion of scientific creation in public classroom curricula, supported by evidence that man and dinosaurs were contemporary [dissertation]. Melbourne, Australia, and Poplar Bluff (MO): Pacific Graduate University. Available on-line at http://home.texoma.net/~linesden/cem/diss/. Last accessed July 26, 2004.

Calais R, Mehlert AW. 1996. Slippery phylogenies: Evolutionary speculations on the origin of frogs. Creation Research Society Quarterly 33 (1): 44-8.

Chittick DE. 1997. The Puzzle of Ancient Man. Tualatin (OR): Precision Graphics.

Cronyn JM. 1990. The Elements of Archaeological Conservation. London: Routledge.

Held J. 1999. Joe's UFO and space mysteries. Available on-line at http://members.tripod.com/J_Kidd/index.html. Last accessed September 10, 1999.

Jochmans JR. 1979. Strange Relics from the Depths of the Earth [booklet]. Lincoln (NE): Forgotten Ages Research Society.

Jochmans JR. 1999. Comments on participation in Mr Noorbergen's work [letter]. http://atlantisrising.com/issue7/letters. html. Last accessed September 22, 1999.

Noorbergen R. 1977. Secrets of the Lost Races. Indianapolis (IN): Bobbs-Merrill Company.

Reheis MJ. 1997. Dust deposition downwind of Owens (dry) Lake, 1991-1994: Preliminary findings. Journal of Geophysical Research 102 (D22): 25 999-26 008.

Steiger B. 1974. Mysteries of Time and Space. Englewood Heights (NJ): Prentice-Hall.

Stromberg P. 1998. Lucy and the ICR: Bearing false witness against thy neighbor. Reports of the National Center for Science Education 18 (5): 28-30.

Wood B. 1999. [Untitled e-mail message.] Available on-line at http://www.ufonet.it/archivio/500000-year-old.htm. Last accessed July 26, 2004.

Willis RJ. 1969. The Coso Artifact. The INFO Journal 1 (4): 4-13.

Per chi desiderasse la versione Inglese di due degli studiosi VERI che si sono dedicati all'esame del "Coso Artifact", ecco lo qui di seguito, con riferimenti bibliografici, non senza l'aggiunta di una mia nota di biasimo per la necessità di perdere tempo prezioso dietro alla caccia dell'oca selvaggia (wild goose hunt) per colpa di colpevoli imbecilli:

The Coso Artifact

Introduction

Creationists have often been criticized for failing to present original research and evidence that would overthrow our contemporary scientific view of human origins. However, this is not entirely fair. The creation "science" field known as OOPARTS, or "Out Of Place ARTifactS", is a lively area of study that relies on "anomalous" finds in the archaeological record to challenge scientific chronologies and models of human evolution. In this paper, we will examine one of the most popular and least understood OOPARTS specimen, the Coso Artifact.The story of the Coso Artifact has been embellished over the years, but nearly all accounts of the actual discovery are basically the same. On February 13, 1961, Wallace Lane, Virginia Maxey, and Mike Mikesell were seeking interesting mineral specimens, particularly geodes, for their LM&V Rockhounds Gem and Gift Shop in Olancha, California. The trio was about 6 miles northeast of Olancha, near the top of a peak about 4300 feet in elevation and about 340 feet above the dry bed of Owens Lake. At lunchtime, after collecting rocks most of the morning, all three placed their specimens in the rock sack Mikesell was carrying (Steiger 1974: 49).

The next day in the gift shop's workroom, Mikesell ruined a nearly new diamond saw blade while cutting what he thought was a geode. Inside the cut nodule, Mikesell did not find the cavity that is typical of geodes, but a perfectly circular section of very hard, white material that appeared to be porcelain. In the center of the porcelain cylinder was a 2-millimeter shaft of bright metal. The metal shaft responded to a magnet. There were other odd qualities about the specimen. The outer layer of the specimen was encrusted with fossil shells and their fragments. In addition to shells, the discoverers noticed two nonmagnetic metallic objects in the crust, resembling a nail and a washer. Stranger still, the inner layer was hexagonal and seemed to form a casing around the hard porcelain cylinder. Within the inner layer, a layer of decomposing copper surrounded the porcelain cylinder.

The Initial Investigations

Very little is known about the initial physical inspections of the artifact. According to Maxey, a geologist she consulted who examined the fossil shells encrusting the specimen said that the nodule had taken at least 500 000 years to attain its present form. However, the identity of the first geologist is still a mystery, and his findings were never published. Another investigation was conducted by creationist Ron Calais. Calais is the only other individual known to have physically inspected the artifact, and he was allowed to record images of the nodule using both X-ray and natural-light photography. Calais's X-rays brought interest in the artifact to a new level. The X-ray of the upper end of the object seemed to reveal some sort of tiny spring or helix. INFO Journal editor Ronald J Willis (1969) speculated that it could actually be "the remains of a corroded piece of metal with threads." The other half of the artifact revealed a sheath of metal, presumably copper, covering the porcelain cylinder.The last individual known to possess the Coso Artifact was one of the original discoverers, Wallace Lane. Lane had the object on display in his home, but he adamantly refused to allow anyone to examine it (Willis 1969). However, he had a standing offer to sell it for $25 000. In September 1999, a national search to locate any of the original discoverers proved fruitless. We suspect that Lane is dead. Maxey is alive, but is avoiding any public comment, and the whereabouts of Mikesell remain unknown. The location and disposition of the artifact are also unknown. Willis's 1969 article is the primary source for information on this object to date.

Fantastic Speculations

Ever since the artifact was first discovered, numerous individuals have speculated about its mysterious origin and possible use. Maxey speculated that the specimen may have been no more than 100 years old after being deposited in a mud bed and sun-baked. However, she also apparently claimed that the artifact could be at least 500 000 years old, "an instrument as old as Mu or Atlantis. Perhaps it is a communications device or some sort of directional finder or some sort of instrument made to utilize power principles we know nothing about" (Steiger 1974).INFO Journal editor Willis speculated that the artifact was some sort of spark plug. His brother found the suggestion extraordinary: "I was thunderstruck," he wrote, "for suddenly all the parts seemed to fit. The object sliced in two shows a hexagonal part, a porcelain or ceramic insulator with a central metallic shaft - the basic components of any spark plug" (Willis 1969). However, they could not reconcile the upper end featuring a "spring", "helix", or "metal threads" with any contemporary spark plug. So the mystery continued. The artifact even appeared briefly at the end of an In Search Of ... episode hosted by Leonard Nimoy.

The internet offers a plethora of other opinions on the subject. While most writers simply report the mystery as described earlier, some have taken to speculating on the purpose and origin of such a device. Brian Wood, describing himself as "Co-Producer, ParaNet UFO Continuum [and] International Director of MICAP [Multinational Investigations Cooperative on Aerial Phenomena]", suggested that if it is not simply a spark plug, "My guess would be some sort of antenna. The construction reminds me of modern attempts at superconductors" (Wood 1999).

Joe Held of "Joe's UFOs and Space Mysteries" thinks that the device "looks similar to a small capacitor with several different materials. The object is roughly the size of an auto spark plug. Since the formation of geodes can take millions of years this was a very curious find indeed" (Held 1999).

The Creationists and the Artifact

With such outrageous speculation, individuals familiar with the creationism/evolution controversy might assume that fundamentalist Christians would stay far away from such artifacts and stories. But this is far from the case. Numerous creationists have been involved with this artifact since its discovery. Calais, who was involved with the Coso Artifact since its initial discovery, is an active contributor to creationist literature (see, for example, Calais and Mehlert 1996). He brought the artifact to the attention of the Charles Fort Society, publisher of INFO Journal. Creation Outreach, a Spokane, Washington-based creationism ministry promotes the artifact on its website by reprinting an article by JR Jochmans which concludes:As a whole, the "Coso artifact" is now believed to be something more than a piece of machinery: The carefully shaped ceramic, metallic shaft and copper components hint at some form of electrical instrument. The closest modern apparatus that researchers have been able to equate it with is a spark plug. However, there are certain features - particularly the spring or helix terminal - that does [sic] not correspond to any known spark plug today (Jochmans 1979).It should also be noted that according to a letter printed in Atlantis Rising, Jochmans claims to have ghost-written three-quarters of the book Secrets of the Lost Races by Rene Noorbergen (1977), which has often been cited as a reference for the Coso Artifact by young-earth creationists (Jochmans 1999). For example, Carl Baugh, a young-earth creationist whose claim to fame is the promotion of the Paluxy River tracks, relies on Noorbergen (1977) in his discussion of the Coso Artifact in his dissertation (Baugh 1989).

Elsewhere in the Pacific Northwest, Institute for Creation Research (ICR) adjunct faculty member Donald Chittick has been heavily promoting the Coso Artifact. In The Puzzle of Ancient Man, Chittick (1997) presents the Coso Artifact as evidence that ancient civilizations were extremely advanced. Presuming that it is an ancient spark plug, Chittick explains his inference that this find indicates technological sophistication. He admits that reliable dates are unlikely, but then goes on to argue that the plug is old because geodes take too long to form. Chittick's discussion assumes that the plug was found inside a naturally occurring geode, which would indicate great age and therefore an "out-of-place" artifact. This, he argues, refutes evolution, since evolutionary models fail to explain the existence of such sophisticated technology so long ago.

The Geologic Evidence: Is the Coso Artifact Encased in a Geode?

When it comes to the geologic evidence, the most stunning claim is that the artifact was discovered in a geode. As Chittick has noted, formation of a geode requires significant amounts of time. But what is often overlooked is that the Coso Artifact possesses no characteristics that would classify it as a geode. The fact that the original discoverers were looking for geodes on the day the artifact was found is not sufficient evidence that the artifact is a geode.Geodes consist of a thin outer shell composed of dense chalcedonic silica and filled with a layer of quartz crystals. The Coso Artifact does not possess either feature. Maxey referred to the material covering the artifact as "hardened clay" and noted that it had picked up a miscellaneous collection of pebbles, including a "nail and washer". Analysis of the surface material using the standard Mohs scale suggests a hardness of Mohs 3, which is much softer than chalcedony.

Other arguments regarding the ancient source of the Coso Artifact focus on the alleged fossil shells encrusted on the surface. If, as noted earlier, a nail and washer were also found on the same surface as the fossil shells, then the power of the inference of an ancient age for the artifact is seriously diminished. Even creationist literature notes how transport, erosion, or other geological changes in surface materials can lead to mistaken assumptions about the true age of individual objects. For example, Creation Ex Nihilo's June-August 1998 issue features fence wire that had become encased by surface materials including "fossil" seashells ([Anonymous] 1998b, quotation marks in the original; see also [Anonymous] 1991, 1998a, 1999).

The Artifact Itself: What Is It?

As noted earlier, numerous individuals have speculated about the identity of the Coso Artifact. The most common suggestion is that it is some sort of spark plug, designed and manufactured by an advanced civilization eons ago for technological devices equal to or surpassing our own. But there is no reason to conclude that the artifact was manufactured thousands of years ago. Some have half-heartedly suggested that the device could have been a contemporary spark plug circa 1961. But ancient artifact proponents point to the X-ray of the top half, which indicates some type of tiny spring or helix mechanism. The content of this X-ray, they argue, runs contrary to what we know about contemporary spark plugs.A clue to what is revealed in the X-ray lies in one of the earliest articles about the artifact. Willis (1969) suggested that the upper end of the object "is actually the remains of a corroded piece of metal with threads." The Willis brothers seriously suspected the object was a contemporary spark plug, but were still unable to explain what was in the X-ray. Spark plugs of the 1960s typically terminated with no visible threading and tapered to a dull point. Though many of the interested parties agreed that the artifact bore a striking resemblance to a 20th-century spark plug, no one seems to have considered the idea of evolution - specifically, spark plug evolution.

Investigating the origins of the Coso Artifact revealed that mining operations were conducted in the area of discovery early in the 20th century. If internal combustion engines were used in these operations in the Coso mountain range, they would have been a very new technology at the time. So we extrapolated that spark plug technology would also have been in its infancy. To help us to learn more about spark-plug technology of a century ago, we enlisted the help of the Spark Plug Collectors of America (SPCA). We sent letters to four different spark plug collectors describing the Coso Artifact, including Calais's X-rays of the object in question. We expected the SPCA to provide some vague hints or no information at all about the artifact. The actual answers were stunning.

On September 9, 1999, Chad Windham, President of the SPCA, called Pierre Stromberg. Windham initially suspected that Stromberg was a fellow spark plug collector, writing incognito, with the motive of hoaxing him. His fears were compounded by the fact that there is an actual line of spark plugs named "Stromberg". Though Stromberg repeatedly assured Windham that his intentions were purely for research, he was puzzled why Windham was so suspicious and asked him to explain. Windham replied that it was so obvious to him that the artifact was a contemporary spark plug, the letter had to be a hoax. "I knew what it was the moment I saw the X-rays," Windham wrote.

Stromberg asked Windham if he could identify the particular make of the spark plug. Windham replied he was certain that it was a 1920s-era Champion spark plug. Later, Windham sent 2 identical spark plugs for comparison. Ten days after Windham's telephone call, Bill Bond, founder of the SPCA and curator of a private museum of spark plugs containing more than 2000 specimens, called Stromberg. Bond said he thought he knew the identity of the Coso Artifact: "A 1920s Champion spark plug." Spark plug collectors Mike Healy and Jeff Bartheld (Vice President of the SPCA) also concurred with Bond's and Windham's assessment about the spark plug. To date, there has been no dissent among the spark plug collectors as to the identity of the Coso Artifact.

Since Windham mentioned that spark plug collectors enjoy pulling pranks on one another, the question of deliberate fraud inevitably crops up in relation to the Coso Artifact. However, there is little hard evidence that the original discoverers intended to deceive anyone from the start. Furthermore, the Spark Plug Collectors of America was formed in 1975, well after the discovery of the artifact, and none of the 3 discoverers was ever affiliated with the organization.

Comparisons and Analysis

On September 14, 1999, Stromberg received a package from Windham containing 2 spark plugs and an analysis of the specimens. Windham wrote:I am enclosing two spark plugs made by Champion Spark Plug company circa 1920s. Plug #1 is 7/8" #18 thread. I have loosely assembled the plug, and chipped the "brass hat" off to show the configuration of it and the porcelain under it. Plug #2 is 1/2" NPT of same design.The most striking aspect of Windham's description is the brass "top hat" that has so vexed previous attempts to provide a rational explanation for the artifact. But other similarities are even more significant. Because Windham had chipped the brass top hat off specimen #1, the spark plug revealed a metal shaft terminating in a flared end, presumably to help to secure the top hat to the plug's porcelain cylinder. The same sort of flared end also appears in the metal shaft of the Coso Artifact. The shaft in the X-ray, just below the flare, also reveals deterioration where it was exposed to the elements above where it meets the porcelain cylinder. This, too, is exactly what we would expect from a 1920s-era Champion spark plug. An X-ray of the specimen that Windham sent us reveals a picture very similar to the original X-ray of the Coso Artifact. As with the original artifact, the central metal shaft of both specimens responds to a magnet.

The diameter of the porcelain on Plug #1 is slightly less than 3/4" - close to the dimension in your letter. As you can see[,] the base and packing nut[,] which hold the porcelain, are sealed with a copper and asbestos gasket. This corresponds with the article. The center electrode of plugs were made of special alloys which were "... cut in two in 1961 but five years afterwards had no tarnishing visible." The sketches included clearly show one rib on the upper end of the porcelain, although Champion used two ribs in this era - probably just an artist's error. The "top hat["] matches those of "plug 1 and 2".

As for the outer shell, it obviously decayed - probably from salt water (or other corrosive substance) [-] and the outer crust is merely some sort of deposit like sea shells or other deposits collected on the deteriorating surfaces of the spark plug base.

There is no doubt that this is merely an old spark plug. Most probably, it is a Champion spark plug, similar to the two enclosed.

Proponents of fantastic stories regarding the artifact have made mention of mysterious copper rings that encase the porcelain. But this too can be easily explained. Windham provided one completely disassembled plug (specimen #1). It revealed a pair of copper rings sandwiching an asbestos lining. According to Windham, this design was necessary because porcelain and steel have vastly differing expansion rates, so the copper was used to compensate for some of the problems this difference caused.

Specimen #2 was not disassembled by Windham, but also presented a feature that could explain why the artifact had not been identified decades ago. Specimen #2, though suffering from severe tarnish, came with a top nut screwed into its top hat. Almost all Champion spark plug advertisements of the first half of the 20th century showed pictures of their spark plugs including the top nut already screwed into place. In some cases, the top nut comes in two forms, one of which closely mimics the tip of today's contemporary spark plugs, which have no threading whatsoever. So it becomes rather easy to understand why the appearance of threads in the Coso Artifact seemed so puzzling to the original investigators.

It should be noted that the corrosion of the Coso Artifact almost completely destroyed any of the iron-alloy-based components, with the exception of the metal shaft encased in the porcelain cylinder. The samples received from Windham also revealed corrosion of the iron-based components, but the brass top hats were unscathed, except for some tarnishing. If the Coso Artifact is indeed a 1920s-era Champion spark plug, the X-ray of an almost perfectly preserved top hat is exactly what one would expect. Brass, a copper-zinc alloy, is commonly engineered to resist corrosion far better than iron-based alloys. In harsh environments, copper tends to outlast iron, but still succumbs fairly quickly. The rates of decay in the Coso Artifact match the rates of decay one would see in a 1920s-era Champion spark plug. An excellent review (Cronyn 1990) of how ferrous and non-ferrous alloys decay over time includes numerous photographs, including X-rays, of contemporary objects that have completely decayed into oxide nodules. Like the Coso Artifact, these examples also feature empty cavities where the original materials once resided.

The formation of the iron oxide nodule probably was hastened by the fact that corrosive "mineral dust" is blown off the dry lake bed of Lake Owen and onto the surrounding uplands where the artifact was discovered. This dust contains salts created by the evaporation of the lake water that are regularly blown off the lake bed by local windstorms. The US Geological Survey has conducted extensive investigations of this phenomena (Reheis 1997).

Reaction from the Paranormal Community

The embrace of the Coso Artifact by young-earth creationists is truly puzzling. We asked the ICR's Donald Chittick why he felt the Coso Artifact was an object worthy of presentation to the public, and specifically how he reconciled a previous age estimate of 500 000 years with his young-earth creationist beliefs. On September 29, 1999, Chittick responded:The article's speculation that it had taken at least 500 000 years to attain the present form is just that: speculation. Actual petrifaction of such objects proceeds normally quite rapidly, as is illustrated by several other similar formations. See for instance, the note about the petrified miner's hat on the back cover of Creation Ex Nihilo (Vol 17, Nr 3) for June-August, 1995. See also an article about another "fossil" spark plug in Creation Ex Nihilo (Vol 21, Nr 4) for September- November, 1999 on page 6.Chittick's revelation that he was already aware of "fossil" spark plugs was startling. We asked in a follow-up letter how he can positively date the Coso Artifact to the Great Flood since he was already aware of contemporary spark plugs that appear to be fossilized. In his response on October 23, 1999, he commented:

You asked what I thought about its age. My best guess is that it is probably early post-Flood. I have not yet been able to obtain sufficient documentation, so I don't say much publicly. However, there is evidence that they did in fact perhaps have internal combustion engines or even jet engines way back then.

It has not been my privilege to personally examine the Coso Artifact or location and strata where it was found. There are two reasons I considered the Artifact significant.As noted earlier, the alleged stratum where the Coso Artifact was found is unknown since all 3 discoverers had separately searched for geodes all morning before consolidating their collections in a single sack. Even if the exact location were discovered, the artifact was an oxide nodule freely lying on the surface, so the stratum where the item was discovered is irrelevant, because surface deposits are an inconsistent mix of eroded, transported, and generally jumbled-up materials that are out of any meaningful geologic or archaeologic contexts.

1. It obviously is a man-made item.

2. Those who evaluated the strata said that it appeared to be old, not modern strata. Those two items are the principle basis for my conclusion that it was worth study. Certainly it does merit further study in my judgment. Numerous items like that abound, but I haven't been able to document them as thoroughly as I would like, and so I don't say too much about them.

Once the investigation revealed beyond a reasonable doubt the true nature of the artifact, Stromberg notified Chittick via postal mail, warning him about the publication of this paper and urging him to issue a retraction and to paste a disclaimer in his book that the Coso Artifact story is fallacious. Chittick never responded, and the second edition of The Puzzle of Ancient Man promotes the Artifact with no disclaimer, but Chittick seems to have stopped mentioning the artifact in his public lectures. When Ken Clark of Spokane's Creation Outreach learned that the Artifact was a 1920s-era Champion spark plug and was offered detailed proof, he ceased to communicate with us. Although Creation Outreach continues to promote the spark plug on its web site by reproducing Jochmans (1979), it adds the editorial note: "Several readers have stated the artifact is indeed a sparkplug from the 1920s" (see http://home.att.net/~creationoutreach/pages/strange.htm).

Conclusion

The Coso Artifact is a remarkable example of how pseudosciences such as "creation science" fail when their analyses and conclusions are investigated in a real-life archaeological situation. Perhaps the most surprising revelation is the stunningly poor research Chittick conducted regarding the Artifact. He persisted in portraying of the Artifact as "ancient" evidence for advanced technology. (RNCSE readers may recall an earlier incident in which Chittick was confronted about his erroneous statements regarding Lucy's knee joint [Stromberg 1998]; his reaction was similar, ignoring warnings and continuing to mislead his audiences.)The Coso Artifact was indeed a remarkable device. It was a 1920s-era Champion spark plug that probably powered a Ford engine, possibly modified to serve mining operations in the Coso mountain range of California. To suggest that it was a device belonging to an advanced civilization of the ancient past could be interpreted as true, but only if we redefine "ancient" to mean "the early 20th century".

Acknowledgments

This article is adapted from a longer, more detailed account of the Coso Artifact that appears on the Talk.Origins Archive web site (http://www.talkorigins.org/faqs/coso.html). This paper would not have been possible without the gracious help from the following individuals: Chad Windham, Bill Bond, Mike Healy, Jeff Bartheld, Arnie Voigt, David Q King, Ken Atkins, Gary L Bennett, Alan Bowes, Linda Safarli, Casey Doyle, Paul Cook, and Ross Langerak.References

Anonymous. 1991. "Fossil" pliers show rock doesn't need millions of years to form! Creation Ex Nihilo 14 (1): 20.Anonymous. 1998a. Bell-ieve It: Rapid rock formation rings true. Creation Ex Nihilo 20 (2): 6.

Anonymous. 1998b. Fascinating fossil fence-wire. Creation Ex Nihilo 20 (3): 6.

Anonymous. 1999. Sparking interest in rapid rocks. Creation Ex Nihilo 21 (4): 6.

Baugh CE. 1989. Academic justification for voluntary inclusion of scientific creation in public classroom curricula, supported by evidence that man and dinosaurs were contemporary [dissertation]. Melbourne, Australia, and Poplar Bluff (MO): Pacific Graduate University. Available on-line at http://home.texoma.net/~linesden/cem/diss/. Last accessed July 26, 2004.

Calais R, Mehlert AW. 1996. Slippery phylogenies: Evolutionary speculations on the origin of frogs. Creation Research Society Quarterly 33 (1): 44-8.

Chittick DE. 1997. The Puzzle of Ancient Man. Tualatin (OR): Precision Graphics.

Cronyn JM. 1990. The Elements of Archaeological Conservation. London: Routledge.

Held J. 1999. Joe's UFO and space mysteries. Available on-line at http://members.tripod.com/J_Kidd/index.html. Last accessed September 10, 1999.

Jochmans JR. 1979. Strange Relics from the Depths of the Earth [booklet]. Lincoln (NE): Forgotten Ages Research Society.

Jochmans JR. 1999. Comments on participation in Mr Noorbergen's work [letter]. http://atlantisrising.com/issue7/letters. html. Last accessed September 22, 1999.

Noorbergen R. 1977. Secrets of the Lost Races. Indianapolis (IN): Bobbs-Merrill Company.

Reheis MJ. 1997. Dust deposition downwind of Owens (dry) Lake, 1991-1994: Preliminary findings. Journal of Geophysical Research 102 (D22): 25 999-26 008.

Steiger B. 1974. Mysteries of Time and Space. Englewood Heights (NJ): Prentice-Hall.

Stromberg P. 1998. Lucy and the ICR: Bearing false witness against thy neighbor. Reports of the National Center for Science Education 18 (5): 28-30.

Wood B. 1999. [Untitled e-mail message.] Available on-line at http://www.ufonet.it/archivio/500000-year-old.htm. Last accessed July 26, 2004.

Willis RJ. 1969. The Coso Artifact. The INFO Journal 1 (4): 4-13.

.jpg)