Ho - abbastanza dissennatamente, lo ammetto - risposto ad un'ennesima provocazione di un sito non allineato, che introduce Jeff Emanuel come il nuovo profeta dei Shardana.

Il mio commento è stato subito cancellato e poi stigmatizzato come non appropriato ed il suo autore (io) come non bene accetto ed invitato a tornare nelle fogne da cui proviene.

Ogni mia replica è stata cancellata immediatamente da un'isterica buttafuori, che immagino abbia istituito una vigilanza h24 sui miei possibili interventi futuri (che non ci saranno, stia pure tranquilla, signora Aba: per la maggioranza degli osservatori la vera fogna siete voi e mi hanno anche rivolto commenti stupiti per avere avuto il coraggio 'tappandomi il naso' di scrivervi).

Ebbene: Jeff Emanuel NON E' AFFATTO UN SOSTENITORE dell'esistenza dei Sherden, in Sardegna come in Canaan (mentre, naturalmente, li ammette in Egitto, servi 'egittizzati' * egli Egizi) e non sostiene affatto, anzi critica molto e su basi scientifiche le idee di Adam Zertal, come non credibili. Eppure, in quel sito 'non allineato' lo portano a riprova della grandezza internazionale degli Sherden...

Riporto di seguito uno dei suoi articoli, in cui l'unica modifica da me apportata è il grassetto ed il corsivo per evidenziare alcune parti di testo e la correzione di 'Torreens' in 'Torreans'.

Chi legge comprenderà meglio come in certe sedi 'non allineate' si tenda a modificare la realtà (gli scritti di alcuni ricercatori seri) secondo i propri desideri (le proprie tesi politiche ed identitarie preferite).

Poi si offendono, se li definisco cumulativamente: "#armatabracaleoneshardariana"... ma per favore.

Sardinians in Central Israel? The Excavator of El-Ahwat Makes His Final Case

THE

UNPRECEDENTED INTERCONNECTIVITY

in the Late Bronze Age (LBA) Eastern

Mediterranean has been the subject of a great deal of study in recent

years. Colloquia, conferences, articles, and monographs have dealt in

depth with the diplomacy, balance of power, and widespread trade that

marked this period and the migrations and collapses that marked the

transition to the Early Iron Age. However, if one archaeologist’s

interpretation is correct, a small site in northern Israel could not

only fill remaining gaps in our knowledge of Late Bronze–Early Iron

communication and migration in the Mediterranean, but turn some of what

we think we know on its head.

The site in question is el–Ahwat, a 7.5–acre “city” near Nahal ‘Iron

in northern Israel, and the archaeologist is the University of Haifa’s

Adam Zertal. A scholar whose previous accomplishments include the

exhaustive two–volume, 1,400–page Manasseh Hill Country Survey

publication (Brill, 2004, 2007), Zertal’s most recent work has the

paradoxical status of being both long–awaited and almost entirely

unheralded. Since 2001, the author has written in various publications

about his belief that el–Ahwat housed a community of Sherden, a ‘Sea

Peoples’ group known primarily from 13th to 11th century Egyptian

records (as well as from some 14th century Ugaritic texts) which are

believed by some to have originated on the island of Sardinia in the

central Mediterranean.

If correct, this interpretation of el–Ahwat would provide direct

evidence for a number of firsts in LBA Mediterranean scholarship. One

example of many is el–Ahwat’s potential status as the first testament to

direct contact between the central Mediterranean and the Levant during

this period (based on current evidence, the exchange that did take place

between eastern and central Mediterranean was likely facilitated by

Cypriot or Mycenaean seafarers).

Another is el–Ahwat’s potential to

serve as the only confirmed site of non-Philistine ‘Sea Peoples’

settlement in the Levant, while striking a blow against the prevailing

scholarly views that the ‘Sea Peoples’ were largely Aegeo-Anatolian in

culture and origin, and that they settled in coastal areas that allowed

for access to the Mediterranean Sea.

However, Zertal’s theories about

the site’s significance and its inhabitants’ origin have either been

largely ignored, or viewed with a detached skepticism until the full

results of the excavation were published.

THE

UNPRECEDENTED INTERCONNECTIVITY

in the Late Bronze Age (LBA) Eastern

Mediterranean has been the subject of a great deal of study in recent

years. Colloquia, conferences, articles, and monographs have dealt in

depth with the diplomacy, balance of power, and widespread trade that

marked this period and the migrations and collapses that marked the

transition to the Early Iron Age. However, if one archaeologist’s

interpretation is correct, a small site in northern Israel could not

only fill remaining gaps in our knowledge of Late Bronze–Early Iron

communication and migration in the Mediterranean, but turn some of what

we think we know on its head.

The site in question is el–Ahwat, a 7.5–acre “city” near Nahal ‘Iron

in northern Israel, and the archaeologist is the University of Haifa’s

Adam Zertal. A scholar whose previous accomplishments include the

exhaustive two–volume, 1,400–page Manasseh Hill Country Survey

publication (Brill, 2004, 2007), Zertal’s most recent work has the

paradoxical status of being both long–awaited and almost entirely

unheralded. Since 2001, the author has written in various publications

about his belief that el–Ahwat housed a community of Sherden, a ‘Sea

Peoples’ group known primarily from 13th to 11th century Egyptian

records (as well as from some 14th century Ugaritic texts) which are

believed by some to have originated on the island of Sardinia in the

central Mediterranean.

If correct, this interpretation of el–Ahwat would provide direct

evidence for a number of firsts in LBA Mediterranean scholarship. One

example of many is el–Ahwat’s potential status as the first testament to

direct contact between the central Mediterranean and the Levant during

this period (based on current evidence, the exchange that did take place

between eastern and central Mediterranean was likely facilitated by

Cypriot or Mycenaean seafarers).

Another is el–Ahwat’s potential to

serve as the only confirmed site of non-Philistine ‘Sea Peoples’

settlement in the Levant, while striking a blow against the prevailing

scholarly views that the ‘Sea Peoples’ were largely Aegeo-Anatolian in

culture and origin, and that they settled in coastal areas that allowed

for access to the Mediterranean Sea.

However, Zertal’s theories about

the site’s significance and its inhabitants’ origin have either been

largely ignored, or viewed with a detached skepticism until the full

results of the excavation were published.

With El–Ahwat: A Fortified Site from the Early Iron Age Near Nahal ‘Iron, Israel (Brill,

2011), the full results of the seven–season excavation are now

available, and the site can be independently studied – as can Zertal’s

theories about its inhabitants and its significance. The

methodically-organized, 27-chapter publication contains over 200

figures, and is comprised of four parts: Stratigraphy, Architecture, and

Chronology; The Finds; Economy and Environment; and Conclusions.

Though each of the former three contains a valuable detailed review of

finds and conclusions related to its subject matter, these portions of

the work sometimes feel as though as though they are serving in large

part to lay the defensive groundwork for Part Four, wherein Zertal uses

the fully published site information to defend the conclusions about the

site that he has been writing about for the last decade.

EL–AHWAT IS LOCATED on the flat shoulder of a ridge ¾ mi. south of the Nahal ‘Iron (Egyptian Arunah,

the ancient route between Egypt and the heavily contested Jezreel

Valley in northern Israel), where it overlooks the Sharon plain, the

Carmel range, and the western Samarian hills. Established on virgin

soil, the view to the north, west, and south provided by el–Ahwat’s

location may have provided a strategic benefit that outweighed poor

resources like a lack of water sources and arable soil (pp. 25, 428).

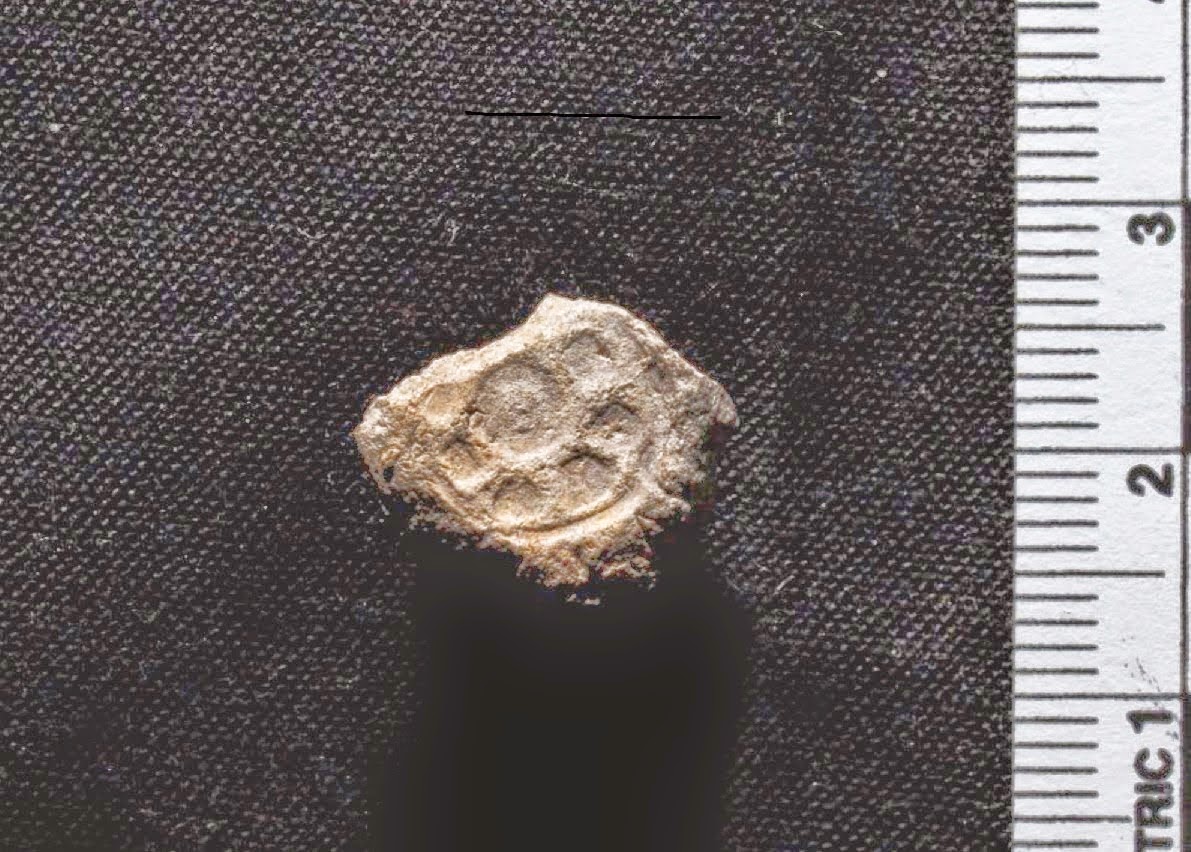

The site has two strata, a late Roman and Byzantine period in which

el–Ahwat was used as a farmstead (p. 41), and a brief (50 to 60 years in

duration [p. 262]) second stratum which the excavator dates from the

late 13th to the early 12th centuries based on pottery, seals and

scarabs (Ch. 14; pp. 233–263, and an beautiful ivory ibex head (Ch. 16;

pp. 288–294). His terminus ante quem for the site’s

inhabitation is a scarab bearing the royal title of the 20th Dynasty

pharaoh Ramesses III (1183–1152 BC [p. 53]); the eight other scarabs

found at the site date to the 19th Egyptian Dynasty (1298–1187 BC). The

chronology of the site will be dealt with in greater detail below.

The site yielded few restorable ceramic finds (Ch. 12), a fact which

for which the excavator credits both the abandonment of el–Ahwat by its

Stratum II inhabitants, and the leveling of that lower stratum for

Roman-Byzantine use (p. 181). However, though lacking in volume, the

site’s ceramic assemblage contained several forms, including bowls

(open, straight-sided, and open carinated), kraters, jugs, cooking bowls

and jugs, jars, beer jugs, collared-rim pithoi (which may have been

used for storing water gathered from the nearest source 1/2 km. away[pp.

424, 428]), as well as chalices, one incense burner and one oil lamp.

All of the pottery at el-Ahwat has parallels in the Levant, though in

Ch. 14, Baruch Brandl notes that el-Ahwat is only the third site in the

Carmel Ridge where collared-rim jars have been found together with New

Kingdom scarabs (p. 263). The bell-shaped bowls (p. 186), a form

associated with Late Helladic pottery and with the intrusive Philistine

culture, were of the locally-made, northern Phoenician variety;

likewise, the pierced loomweights found at the site (p. 200) follow in

the standard Levantine tradition, rather than being of the rolled and

unbaked style associated with the Cypro-Aegean Philistines and other

‘Sea Peoples’.

El–Ahwat is architecturally divided into four Areas, or “quarters,” A

through E (A and B are portions of the same “quarter), with “quarter

walls” running between each section. Area A contained the city’s gate

(a small, thin door mounted on a doorpost [p. 62]), a terrace with an

administrative complex (Complex 100 [p. 79]), and a

unique isosceles triangle-shaped “approach” to the city gate, which

Zertal and chapter co-author Ron Be’eri reconstruct as having a small

opening to the outside at the base of the left leg, then allowing

traffic to widen within the approach before funneling into the gated

entrance at the triangle’s pinnacle (pp. 62-64). Area C contained a 510

sq m residential complex (which chapter author Nivrit Lavie–Alon notes

is “among the largest continuous quarters exposed by Israeli

archaeology” [p. 124]), within which two oil presses were found in

addition to valuable small finds, including several scarabs. A furnace,

possibly for iron forging (p. 383) was found in Area D, along with two

free-standing corbeled-roof “huts” or silos, which chapter author Amit

Romano suggests may indicate its status as “the center for an industrial

craft or some sort of metal processing” (p. 157). Due to a lack of

material finds other than walls, chapter author Lavrie–Alon suggests

that Area E was used as an enclosure for livestock (p. 161).

It is the architectural perimeter of the site that has most

contributed to the excavator’s conclusions about its purpose and its

inhabitants. El–Ahwat is quite irregular in shape, with an “undulating”

(p. 32), somewhat–ovular “city wall” encircling it in wavy fashion.

This wall contains several large rock mounds that the author refers to

as “towers” despite their unclear function (p. 38) and the likelihood

that few actually served as such (save perhaps T1 and T2, which sit

outside the wall to the west, and T53, which is built into the eastern

portion of Area D), and has built into its structure four of what Zertal

identifies as “corridors” (p. 412). In addition to these corridors,

several “igloo-like stone huts” which the author identifies as

“false-domed tholoi” are either free-standing constructions or

are built into the wall itself (such as U409 in Tower 53 [Area D], which

is entered by one of the “corridors” [p. 413]). For Zertal, these

corridors and tholoi combine with the outer wall to give el–Ahwat its greatest uniqueness and significance.

IF PARTS 1–3 of this volume lay the groundwork for Zertal’s defense

of his theories about the site, Part Four does not disappoint, as the

author uses the majority of the final section to argue for Sardinian

influence on, and Sherden inhabitation at, el–Ahwat.

To the author’s

eye, “the plan of el–Ahwat differs from anything known elsewhere in the

Levant. Judging by its design and unique features, the architects of

el–Ahwat seem to have planned the site according to a master plan based

on earlier architectural traditions” (p. 28). It is the location the

author sees as being the origin of these “earlier architectural

traditions,” and the conclusions he draws from it, that make el–Ahwat a

controversial site, and this final report a controversial publication.

Zertal compares the site’s “undulating” wall, corridors, tholoi, inner dividing walls, and free-standing corbeled stone “huts” (U409 and U461), to the proto–nuraghe

of Bronze Age Sardinia and the 13th century BC Toreanic [l'autore scrive 'toreenic'] Culture of

neighboring Corsica (pp. 415–423), and suggests that this architectural

style was brought to the Levant by immigrants from the central

Mediterranean.

Though he has previously stipulated that a

lack of other diagnostic finds, such as Sardinian pottery, means the

journey was likely circuitous and time–consuming enough that it resulted

in acculturation to some degree along the way, this remains an issue

for Zertal’s conclusions, as the material culture of el–Ahwat is

entirely Canaanite in nature (with Egyptian small finds included),

blending hill country and lowland traditions in a site that, save for

the meandering outer wall with its corridors, is largely typical of

northern Canaan in the Iron I.

This stands in marked contrast to the

Philistine material culture footprint (to date, the only known ‘Sea

Peoples’ material culture), which consists not only of site

architecture, but of intrusive ceramic, cultic, and domestic traditions

that prove beyond doubt the presence of an intrusive culture at their

major sites.

The wall itself is another question. While it may be that Zertal is

correct, and the site’s 600 m long, 6 m high, and 5 m thick wall may

have served, along with its “towers,” as massive fortifications, he

acknowledges that it appears to have been “built in ‘patches’ and

‘sections’” (p. 412), a possible indicator that this structure is

neither as cohesive nor as temporally constrained as the author imagines

it to be.

As the remains of the city wall rise above the entirety of

the site’s second (Iron Age) stratum, it is possible that what appears

now to be the remnant of a massive fortification was constructed as a

retaining wall or terrace during the Roman-Byzantine occupation in

Stratum I, and the awkward contouring of rooms to the wall lacks the

appearance of planned construction. This can particularly be seen on

the western edge of Area C1, where a small unnamed and evidently unused

gap appears north of W4313, and where L3328 appears to be a much larger

gap between the area’s architecture and the wall. In the western

portion of Area D, “quarter wall” 3410 appears to intrude on the area’s

architecture (cf. p. 47), and the unique “approach” in Area A2 seems too

awkward – and too likely to have caused logjams between the outer and

inner entrances – to have been a planned feature of the Iron Age city.

Further, Tel Aviv archaeologist Israel Finkelstein has pointed out that

the “corridors” in the wall are comparable to well–known highland field

towers used for storage and for habitation (IEJ 52: 189).

The issue of the Sherden is more theoretical in nature (their

association with Sardinia is itself solely the result of linguistic

resemblance), but Zertal dedicates a portion of Part Four to reviewing

some of the evidence for their presence and activity in the Near East at

this time.

Unfortunately, he provides an incomplete selection and a

selective interpretation of that evidence, choosing to read it in the

way that best supports his theory while ignoring those portions that

detract from his point.

On p. 431 he references the Papyrus Harris I,

which lists the Sherden among the invading ‘Sea Peoples’ defeated by

Ramesses III and supposedly settled in Egyptian fortresses at home or in

Canaan. However, P. Harris I is a much later account of the Year 8

invasion, and the inscription at Ramesses III’s mortuary temple at

Medinet Habu, which was written at least twenty years earlier (and only a

few years after the event itself) contains no mention of the Sherden

among the sea or land invaders.

On pp. 432–433, Zertal references the Onomasticon of Amenope,

an 1100 BC list of peoples and places in the Near East that mentions

three Philistine cities followed by three ‘Sea Peoples’ groups (Sherden,

Sikil, and Philistines), as evidence that Ramesses III had settled the

Sherden to the north of Philistia and of the port city of Dor, which the

contemporary Tale of Wen–Amon refers to as the “Harbor of the Sikil.” However, the Onomasticon

is a cryptic text which is filled with lacunae, and which contains

almost no context regarding the orientation or ordering of its toponyms

and ethnika, thus making any attempt to use it as a map of ‘Sea

Peoples’ settlements a risky endeavor at best. Any effort to securely

place non–Philistine ‘Sea Peoples’ anywhere in Canaan is difficult at

best, as no material culture template is currently available for the

other members of this seafaring coalition.

The Sherden are no

different; the centuries of evidence for their presence in Egypt are

complemented by an almost total lack of evidence for their presence in

Canaan, aside from three possible mentions in letters from the 14th

century.

THE CHRONOLOGY OF the site, as noted above, is also problematic – a fact Zertal et al address

directly. Though the authors of this volume put the ceramic and

glyptic evidence from el–Ahwat firmly in the late 13th and early 12th

centuries, recent radiocarbon analysis of olive pits from the site

returned a date range of 1057–952 BC, suggesting that the dates of

inhabitation should be lowered by two hundred years. Even if the early

date of 1057 is considered as the final year of the site’s inhabitation,

the 50–60 year duration of the site’s inhabitation proposed by

Zertal et al would put el–Ahwat’s founding in the final quarter of the

12th century – at least a half century short of the author’s

proposed terminus ante quem for the site.

In Ch. 3, Zertal argues that the 14C dates should be ignored on the

basis of what he sees as a close correlation between the material finds

and corresponding Egyptian archaeology, as the latter is firmly enough

known to be impervious to radiocarbon results from a small site in

central Israel. In doing so, he rejects the possibility that the

Egyptian objects found at the site, which date to the 14th–12th

centuries, were brought to el–Ahwat at a later date as amulets or

objects of other perceived value (though even if the site was founded in

the late 13th century, some of the Egyptian objects found there would

already have been a century old or more at the time of their arrival).

Instead, he argues – on the basis of continue olive cultivation in the

vicinity after inhabitation had ceased – that the olive pits selected

for testing “could have been introduced there at any time after the site

was abandoned in the 12th century BCE” (p. 53).

El–Ahwat’s potential Sardinian connection brings with it another

chronological problem.

While the construction of hybrid, “Canaanized”

proto–nuraghe could have been carried out by individuals who had

traveled to Sardinia in the Late Bronze II and brought that “template”

back with them to the Levant, Zertal argues that the small number of

sites fitting el–Ahwat’s mold makes this unlikely, writing that

“this…possibility is much less plausible for the simple reason that

their presence is limited to only four or five sites in 13th–12th

century Canaan. Such limited influence is better explained by

‘colonies’ of immigrants, who brought with them some of their old

traditions, rather than by influence derived through trade” (p. 423).

However, proto–nuraghe of the type that Zertal suggests el–Ahwat’s

fortifications were patterned after date to the 18th–16th centuries BC; following this time, in the early–middle Nuragic period, there is little

evidence on Sardinia of foreign contacts.

While communication with the

wider Mediterranean, including the Aegean and Cyprus, grew rapidly in

the LB II, Sardinians traveling abroad at this time who sought to build

settlements similar to the nuraghe of their home island would likely

have constructed the corbel–vaulted nuragic type dwellings which were

being made in Sardinia at that time, rather than the

“false–domed tholoi” Zertal suggests were built at el–Ahwat.

Interestingly absent from this volume is any discussion of Zertal’s theory that el–Ahwat was the biblical Harosheth Haggoyim,

the base of the Canaanite King Jabin’s nine–hundred–strong chariotry

under the command of Sisera in the biblical story of Deborah (Judges

4–5). In a 2010 press release,

Zertal championed the possible identification of a chariot linchpin

fragment from Area A3 as “[proof] that chariots belonging to

high-ranking individuals were found” at el–Ahwat, despite

its remote, rugged location, and as evidence “that this was Sisera’s

city of residence and that it was from there that the chariots set out

on their way to the battle against the Israelite tribes.”

In this site report, by contrast, the only mentions of chariots in

the entire volume (by my count) were made in Ch. 17, which deals with

the possible linchpin fragment. The bronze shard in the shape of a

female head, which at 2 cm high, 1.6 cm wide, and only 3 mm thick is far

thinner, if only slightly smaller in surface area, than the 10 mm thick

chariot linchpins from 11th- and 10th-century Ekron and Ashdod that

chapter author Oren Cohen uses as comparanda. As a result of this

fragment’s relative frailty, Cohen writes, “it is difficult to establish

whether the linchpin…was used for a full-scale chariot or was part of a

smaller, cultic feature” (p. 300). In all, this volume deals with

Zertal’s theories about el–Ahwat’s Sardinian connection in a much more

measured fashion than some of his previous publications have. Cohen’s

sober analysis of the bronze fragment fits well with the tone of a final

excavation report, but it stands in sharp contrast to Zertal’s previous

statements about the site and about this particular artifact.

THE FINAL PUBLICATION of the el–Ahwat excavations is valuable for its

straightforward presentation of the architecture and material culture

of this short-lived site. Though several passages in the volume can be

read as defenses of Zertal’s conclusions about the site’s influences and

chronology, the finds are allowed to speak for themselves to a

sufficient degree that scholars will be able to draw their own

conclusions about el–Ahwat from the material itself, rather than simply

from the excavator’s assertions (as had previously been the case with

this site).

Further, whether the site truly represents an architectural link with

the central Mediterranean and the first material evidence of

non–Philistine ‘Sea Peoples’ settlement in the Levant or not, el–Ahwat

is a unique site in many ways, not least of which are its remote

location (far from water, arable soil, and traveled roads [pp. 413,

435]) and its brief Iron Age duration, which allows it to serve as a

rare single-stratum snapshot of settlement (or, in Zertal’s words, a

“‘time capsule’…of the period” [p. 3]). As such, though its legacy may

be that of an outside-the-mainstream argument for ‘Sea Peoples’

settlement in the Levant, and though its steep price will confine its

circulation almost exclusively to research libraries, this final

publication of el–Ahwat will hold great value for those

studying settlement, architecture, and change in the hill country

culture of Iron Age Canaan.

* C'è un'ameba che si è sentita offesa dall'espressione 'schiavi egittizzati' da me usata per i Sherden viventi in Egitto. A perte il fatto che l'espressione - che io pienamente condivido - non è stata coniata da me, credo che soggetti che si stabiliscono in Egitto, prendono una moglie Egiziana, prendono un nome egizio ed adottano religione usi e costumi egizi,

sono sicuramente egittizzati. Il fatto poi che siano stati

indotti a trasferirsi e stabilirsi in Egitto, in zone di confine, (

per servire da 'cuscinetto' ad eventuali tentativi d'invasione o d'occupazione da parte di immigrati clandestini),

non ne fa certamente dei padroni, bensì dei servitori.

Poche cose m'infastidiscono di più di qualcuno cui s'indica la luna e puntualmente guarda il dito.

°Chi è Jeff Emanuel: Harvard University,

Center

for Hellenic Studies, CHS Fellow (Fellow del Centro di Studi Ellenici) in

Aegean Archaeology and Prehistory

Autore di 23 tra articoli

scientifici, poster e comunicazioni, due libri, e 10 commenti su libri

scientifici di altri.

El–Ahwat: A Fortified Site from the Early Iron Age Near Nahal ‘Iron, Israel, edited by Adam Zertal (ISBN 978–9004176454; 485 pages; $185), is published by Brill.