Using modern human genetics to study ancient phenomena

Anthropology, Breakingnews, Genetics, Human Evolution

We humans are obsessed with determining our origins, hoping to reveal a little of “who we are” in the process.

It is relatively simple to trace one’s genealogy back a few generations, and there are many companies and products offering such services.

But what if we wanted to trace our origins further on an evolutionary timescale and study human evolution itself? In this case, there are no written records and censuses. Instead, the study of human evolution has so far relied heavily on fossil specimens and archaeological finds.

Now, genetic tools and approaches are frequently used to answer evolutionary questions and reveal patterns of divergence that reflect different selective pressures and geographical movement.

This is particularly true for studies of human migrations out of Africa, global population divergence, and its consequences for human health.

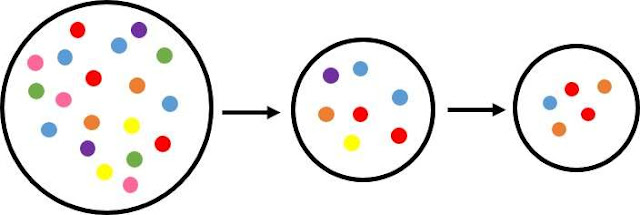

Figure 1. Diagrammatic representation of the serial founder effect model

[Credit: Emma Whittington]

Humans Originated in Africa

The current best hypothesis suggests anatomically modern humans (AMH) arose in East Africa approximately 200,000 YBP (Years Before Present).

AMH migrated from Africa around 100,000-60,000 years ago in a series of dispersals that expanded into Europe and Asia between 60,000 and 40,000 YBP.

It has been scientifically proven that East Africa is the origin of humans, and supported by both archaeological and genetic data.

Genetic diversity is greatest in East Africa and decreases in a step-wise fashion from the equator in a pattern reflecting sequential founder populations and bottlenecks.

Figure 1 shows three populations with decreasing genetic diversity (represented by the colored circles) from left to right. The first population, with the greatest genetic diversity, represents Africa. A second population is shown migrating away from ‘Africa’ taking with it a sample of the existing genetic diversity. This forms the founding population for the next series of migrations. Each time a population migrates it represents only a sample of genetic variation existing in its founding population, and in doing so, sequential migration (such as those in Figure 1) leads to a reduction in genetic diversity with increasing distance from the first population.

Leaving Africa – Where do we go from here?

Although the location of human origin is generally accepted, there is a lack of consensus around the migration routes by which AMH left Africa and expanded globally.

There are many studies using genetic tools to identify likely migration routes, one of which is a recent PLOS One article by Veerappa et al (2015).

In this study, researchers characterized the global distribution of copy number variation, which is the variation in the number of copies of a particular gene, by high resolution genotyping of 1,115 individuals from 12 geographic populations, identifying 44,109 copy number variants (CNVs).

The CNVs carried by an individual determined their CNV genotype and by comparing CNV genotypes between all individuals from all populations, the authors determined similarity and genetic distance between populations.

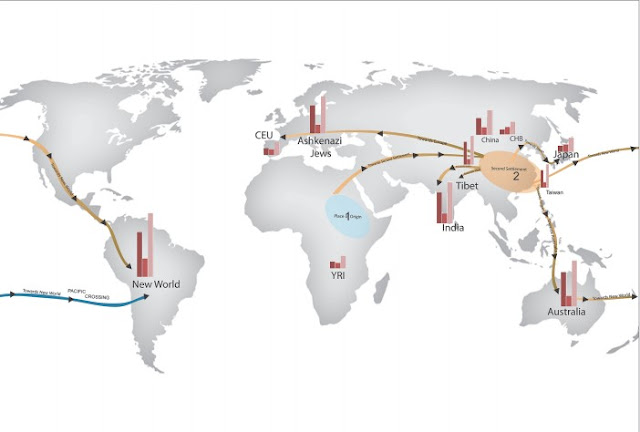

The phylogenetic relationship between populations proposed a global migration map (Figure 2), in which an initial migration from the place of origin, Africa, formed a second settlement in East Asia, which is similar to a founding population seen in Figure 1.

At least five further branching events took place in the second settlement, forming populations globally. The migration routes identified in this paper largely support those already proposed, but of particular interest this paper also proposes a novel migration route from Australia, across the Pacific, and towards the New World (shown in blue in Figure 2).

[Credit: Veerappa et al (2015)]

Global Migration Leads to Global Variation As AMH spread across the globe, populations diverged and encountered novel selective pressures to which they had to adapt. This is reflected in the phenotypic (or observable) variation seen between geographically distant populations.

At the genotype level, a number of these traits show evidence of positive selection, meaning they likely conferred some advantage in particular environments and were consequently favored by natural selection and increased in frequency.

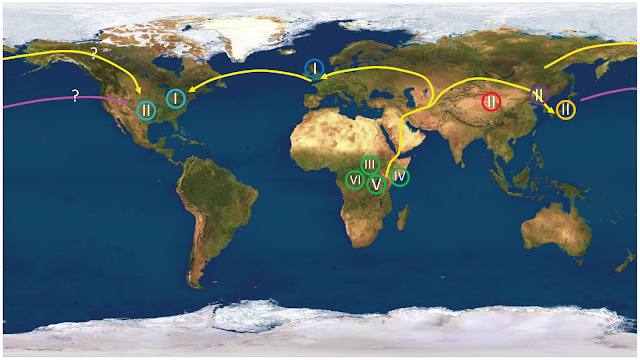

A well cited example of this is global variation in skin color, which is thought to reflect a balance between vitamin D synthesis and photoprotection (Figure 3).

Vitamin D synthesis requires UV radiation, and a deficiency in vitamin D can result in rickets, osteoporosis, pelvic abnormalities, and a higher incidence of other diseases.

At higher latitudes, where UV radiation is low or seasonal, experiencing enough UV radiation for sufficient vitamin D synthesis is a major concern.

Presumably, as AMHs migrated from Africa, they experienced reduced levels of UV radiation, insufficient vitamin D synthesis, and severe health problems; resulting in selection for increased vitamin D synthesis and lighter skin pigmentation.

Consistent with this, a number of pigmentation genes underlying variation in skin color show evidence of positive selection in European and Asian populations, relative to Africa.

On the flip side, populations near the equator experience no shortage of UV radiation and thus synthesize sufficient vitamin D; however the risk of UV damage is much greater. Melanin, the molecule determining skin pigmentation, acts as a photoprotective filter, reducing light penetration and damage caused by UV radiation, resulting in greater photoprotection in darkly pigmented skin.

Selective pressure to maintain dark pigmentation in regions with high UV radiation is evident by the lack of genetic variation in pigment genes in areas such as Africa.

This suggests selection has acted to remove mutation and maintain the function of these genes.

Figure 3. A map showing predominant skin pigmentation globally

[Credit: Barsch (2003)]

Can genetics and human evolution have a practical use in human health?

Beyond phenotypic consequences, genetic variation between populations has a profound impact on human health.

It has a direct influence on an individual’s predisposition for certain conditions or diseases. For example, Type 2 diabetes is more prevalent in African Americans than Americans of European descent.

Genome wide association studies (GWAS) analyze common genetic variants in different individuals and assess whether particular variants are more often associated with certain traits or diseases.

Comparing the distribution and number of disease-associated variants between populations can assess if genetic risk factors underlie disparities in disease susceptibility. In the case of Type 2 diabetes, African Americans carry a greater number of risk variants than Americans of European descent at genetic locations (loci) associated with Type 2 diabetes.

It is clear that an individual’s ethnicity affects their susceptibility and likely reaction to disease, and as such should be considered in human health policy.

Understanding the genetic risk factors linking populations and disease can identify groups of individual at greater risk of developing certain diseases for the sake of prioritizing treatment and prevention.

Applying modern human genetics to human evolution has opened a door to studying ancient evolutionary phenomena and patterns.

This area not only serves to quench the desire to understand our origins, but profoundly impacts human health in a way that could revolutionize disease treatment and prevention.

In this blog, I have given a brief overview of how using genetic approaches can tell us a great deal about human origins, migration and variation between populations.

In addition, I have outlined the complex genetic underpinnings behind ethnicity and disease susceptibility, which suggests an important role for population genetics in human health policy.

This blog post covers only a fraction of the vast amount of ongoing work in this field, and the often ground breaking findings.

It is unclear exactly how far genetics will take us in understanding human evolution, but the end is far from near. The potential for genetics in this field and broader feels limitless, and I for one am excited by the prospect.

Author: Emma Whittington | Source: PLOS Blogs [August 01, 2015]

Author: Emma Whittington | Source: PLOS Blogs [August 01, 2015]