Chissà poi perché non parlano di Sciardana....

5,000-year-old fort found in Monmouth

ArchaeoHeritage, Archaeology, Breakingnews, Europe, UK, Western Europe

Archaeologists in Monmouth have discovered the remains of an ancient wooden building that dates back 5,000 years.

An artist impression of what the fort looked like nearly 5,000 years ago

[Credit: Monmouth Archaeological Society]

Steve Clarke, who two years ago uncovered the remains of a huge post-glacial lake at the Parc Glyndwr building site, said the timber remains found under the new Rockfield estate were once part of a crannog, an ancient fortified dwelling built into a lake.

Part of the wooden building set into the bed of what was once Monmouth’s prehistoric lake, pre-dates the only other known crannog in England and Wales by 2,000 years.

The New Stone Age timber (Neolithic), which was skilfully worked with a stone axe, was unearthed during the digging of house foundations at Jordan Way off Watery Lane by Martin Tuck of the Glamorgan Gwent Archaeological Trust in 2003 while overseeing the construction of the estate.

It was preserved beneath the clay and peat of a lagoon which formed when the lake drained some 2,000 years ago and was recently given to Monmouth Archaeological Society whose professional wing- Monmouth Archaeology- is to be the archaeological unit covering the construction of 450 new homes on Wonastow Road.

A slab of timber was discovered when the estate was constructed in 2003 [Credit: Monmouth Archaeological Society]

The timber was sent to the Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre in Glasgow for a radiocarbon study to be carried out which produced a date of 2,917 years BC.

The study took several months and was funded by the Monmouth Society. Mr Clarke, 72, who is the chairman and founding member of Monmouth Archaeological Society, said it is a very important and exciting discovery.

“This is only the second one in England and Wales, the other being at Llangorse Lake, near Brecon.”

“The timber, bearing cut marks left by stone or flint axes, formed the end of an oak post which had been carefully levelled to create a flat surface which would probably have rested on a post pad set in the bottom of the lake.”

A reconstructed crannog at Llangorse Lake, Wales

[Credit: Monmouth Archaeological Society]

“Archaeologists are excited, not only by the state and date of the timber, but also because the remains were so far out from the shore of the lake that the post has to be part of a building set on poles- called a crannog.”

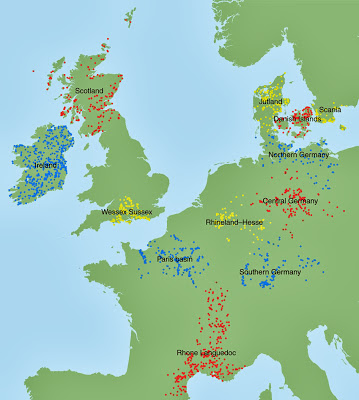

Crannogs are defended wooden structures found in Ireland and Scotland and date from the Stone Age onwards.

They are thought to have been a mark of power and status- the one at Llangorse being claimed as a royal residence of the Dark Age King of Brycheiniog.

“Martin realised the importance of the timber and kept it in water before handing it to us for our archives,” said Mr Clarke.

Author: Kath Skellon | Source: Free Press

[July 22, 2015]

.jpg)