Abusing the past – Bad Archaeology

For many people, archaeological evidence – the physical remains of the past – are the ultimate proof of “what happened in history”.

Even a radical post-modernist cannot deny the physical existence of objects or buildings, so they can be presented as incontestable relics to be trotted out to prove one’s point and to illustrate the ‘truth’ of assertions about the past.

And this is where the trouble starts. In reality, the remains of the past are highly contestable: witness the uses to which archaeological data have been put by political and religious extremists from Nazi Germany to Hindu fundamentalists, from Christian evangelicals to Bosnian nationalists, and you will soon appreciate how easy it can be to appropriate the past and twist it to suit specific agendas.

Egregious examples like these are easy to spot. It is more insidious when those with less strident aims twist archaeological data to their own ends. Think of the infiltration of popular culture with ideas about the supposed mysteries of Ancient Egyptian pyramids, the existence of ley lines or the drowned continent of Atlantis. Television, especially, accepts many of these ideas uncritically, and promotes them through glossy ‘documentaries’ and more subtly through their incorporation as if fact into drama.

Vulgar errors

At the lower end of the scale of abuse, many commonly held beliefs promote wrong ideas about the past. Was every English parish church really built on the site of a place of pagan worship? To read some authors, including those who write local history booklets and community websites, you would certainly think so. Although some churches rest on re-used Roman masonry, there is little evidence to suggest that this had any pagan associations, and in most cases, there is no evidence for an earlier religious use of the site.

Some utterly silly ideas have passed into the common currency of what we may think of as folk wisdom. Ley lines, despite being a modern conceit, have passed into received wisdom. Originally conceived as ‘Neolithic pathways’ by their inventor, Alfred Watkins, they were hijacked by the counter-culture of the 1960s as lines of ‘energy’ (one of those ‘subtle energies’ that resist all attempts at measurement except by psychic means), used as navigational aids by flying saucers. Their crossing-points are supposed to have been recognised as powerful places by ancient peoples, who sited their monuments upon them (or, according to some, created the monuments to channel the ‘energy’). Even BBC News has been known to refer to ley lines as if there is no question about their existence. They are utter tosh, of course, and no credible evidence for their existence has ever been produced.

Things that you’re li’ble to read in the Bible

Early in its development, archaeology was seen as a tool that would help amplify what the Bible tells us about the past and to confirm its narrative. Although the early signs were encouraging, it eventually became clear that many of the stories contained in the Hebrew Bible could not literally be true. It was not just the big things, like a worldwide flood in the twenty-fourth century BCE, but also little details such as the length of reign of Belshazzar (he of the graffiti scandal) that fell to the irresistible logic of independent data. There were two responses to what archaeology appeared to say about the past of the Middle East: either accept that the Bible was a human product, complete with all the inaccuracies and propagandist retellings that would involve, or it was the infallible word of god and the archaeological data must be wrong.

The second response was to lead to one of the most insidious of all abuses of the past: the concept of Biblical (and Qur’anic) inerrancy. Under the guise of creationism (or its noms-de-plume ‘scientific creationism’ or ‘intelligent design’), it inculcates a complete way of understanding the world that flies in the face of rationality. At the same time, it has inspired numerous amateurs to go out in search of Noah’s Ark and other such elusive objects.

The formation on the slopes of Mount Kalinbabada near Doğubayazit were once believed to be Noah’s Ark

The question that few of these people seem willing to address is why should we expect things that are said to have existed more than four millennia ago still to exist (and to exist in an instantly recognisable form)? What right do we have to expect the treasures of the Temple of Jerusalem to be hidden away somewhere, awaiting their rediscovery? Why wouldn’t the Romans who captured them in 70 CE have melted them down for their gold and silver?

Artefacts that shouldn’t exist

One of the most enduring classes of ‘mystery’ touted by the authors who deal in alternative views of the past is the so-called out-of-place artefact. Many of them are familiar enough: the spark plug encased in a geode, the Mexican crystal skulls, the Turin shroud. Some of them can appear to be impressive evidence that the experts don’t know everything and, indeed, some of them are genuinely intriguing.

Most, though, are not. The ‘Bimini road’, for instance, is not a part of lost Atlantis but a natural formation of beach rock. A ‘Neanderthal shot with a bullet’ is neither Neanderthal nor shot but a Homo rhodesiensis fossil with a pathological lesion. The ‘Dropa stones’ do not tell of the arrival of aliens in western China twelve thousand years ago, as they were first heard of in a short story published in 1960 and never existed outside it. The rust-free iron pillar in the Qutb Minar mosque near New Delhi is not evidence for alien visitation but was made for King Chandragupta II Vikramaditya (c 376-415 CE) and owes its condition to the purity of the ore from which the iron was smelted.

The problem with this type of evidence is that fringe writers cite large numbers of such objects (sometimes just as lists of supposedly anomalous artefacts) that leave an overwhelming impression on the reader that standard accounts of human development must be wrong. The sheer weight of numbers makes them difficult to refute: each object has to be considered in turn and numerous works by specialists must be consulted before a more critical reader is able to assess them more fully. It almost goes without saying, that no ‘out-of-place artefact’ has ever been shown either to be anomalous at the time it was created or not based on misinterpretation of the evidence.

The crystal skull. Collection of the British Museum in London. : Image Source : Wiki Commons

“New Age” vibes

The 1960s saw wholesale transformations of western society and culture, some brought about by the technological changes that had been accelerating since the Second World War and others brought about by an increase in overall prosperity. Beginning in the 1950s with Beatnik youth culture, young adults came increasingly to dominate those media that were the principal sources of information for the public at large. The media narratives ranged from scare stories about ‘reefer madness’ to rumours about the love lives of pop stars. Much of the time, they dealt with the developing counter-cultures that were embraced by the young. Although the origins of these counter-cultures go back to the occult revival of the later nineteenth century and beyond, it was only in the 1960s that they became a staple of popular discourse and part of a growing anti-authoritarian attitude.

By the end of the 1960s, the different counter-cultures had begun to coalesce around what was proclaimed as the “New Age”, the dawning Age of Aquarius that would raise humans to a new and unprecedented level of spiritual consciousness (not that anyone can agree when the Age of Aquarius is supposed to begin). There was a sense that this involved a return to a ‘lost’ state of innocence. Quite when we lost our ‘innocence’ varies according to the viewpoint. Some radical feminists thought that the development of metallurgy brought with it patriarchy and the destruction of all that was noble in humanity; some back-to-nature types thought the development of agriculture was to blame; others thought that rising sea levels at the end of the Pleistocene destroyed a civilisation that successfully combined advanced technology with deep spirituality.

In these views, decisions made in the past were directly responsible for the woes of the present. To ‘heal’ society would involve the rediscovery of these ancient beliefs in the universal mother, the abandonment of western technology or some other aspect of the modern world to which the author takes exception.

Ancient astronauts?

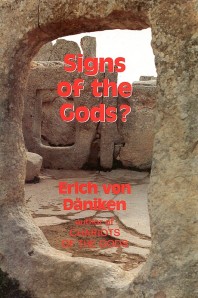

When I was young, an English Sunday newspaper serialised Erich von Däniken’s Chariots of the Gods?, bringing the idea that aliens had a hand in the development of human civilisation to a wide audience. It was in the heady days of the Apollo moon missions, when space travel seemed on the verge of becoming an everyday occurrence. Ancient astronauts sounded feasible and the idea took off rapidly (no pun intended).

The problem with the idea was that it relied on a small number of artefacts and sites to provide the evidence in its favour. They were widely separated in time and space (from the Ice Age to the Middle Ages, from Egypt to Mexico to China) and they were not unequivocal evidence, such as parts of a spaceship or technological objects not of human manufacture. Instead, we were treated to the idea that Egyptians could never have built the pyramids with the technology available to them (they could, of course), that a sarcophagus lid in Tikal, Mexico, shows the pilot of a space capsule (actually the descent of the Lord Pacal into the underworld) and that references in ancient literature to fiery chariots were eyewitness descriptions of spacecraft.

Because the ancient astronaut believers only ever dealt with selected bits of evidence, they were not mounting a serious challenge to our views of how ancient societies worked, how their technological accomplishments developed through time, how human cultures adapt and change. It was felt to be safe to ignore this challenge to accepted accounts of the past.

This was a mistake. To numerous authors, the lack of a response from archaeologists was proof that they couldn’t answer the challenge. In reality, they thought that it was beneath their dignity to do so. The academic discipline of archaeology refines its understanding of the past by admitting a great deal of diversity in how we explain the past, so that no two books will tell precisely the same story, nor should they. By disagreeing over the details, we can improve hypotheses by exploring the weak spots and flaws in what is already believed.

Alternative methodologies

This is also how people like von Däniken try to present themselves and their ideas: as mavericks nibbling away at the poorly understood edges of knowledge. An examination of their methods soon undermines this view. They tend to avoid the basic core knowledge (after all, who wants to have to learn about animal husbandry or pottery production when there is money to be made from speculation?), so that their nibbling at the edges in fact pushes those edges to the forefront in their writings. In doing so, they set up a completely separate methodology for examining the past.

One of the features of this approach is that its proponents often claim to have a single explanation for all ancient ‘mysteries’. Some explain them in terms of space aliens, others in terms of a ‘lost civilisation’, others by lost human faculties or a lost technology. This insistence on single explanations is very similar to writers on all sorts of other mysteries, from UFOs to ghosts to the fate of the Romanov dynasty.

These writers have a tendency to cherry-pick only those data that will support their ideas rather than present a rounded picture of ancient societies. Their hope is that they can use these supposedly anomalous data to destroy conventional views of the past in the minds of their readers, but they fail to follow up the consequences of accepting these ideas. What would be the implications for our understanding of human history if it could be shown that the ‘gods’ of Sumeria were really aliens from Nibiru, who created humans as slaves? This should have profound implications not only for how we understand Sumerian history in the third millennium BCE, but also how we understand ourselves. These deeply unsettling implications seem less important to their proponents than the expert-bashing that gains them a wide readership,

But they would say that, wouldn’t they?

There is something in the mindset prone to swallowing these wrong ideas about the past that is wide open to seeing conspiracies everywhere. Did the Knights Templar survive their alleged suppression in the early fourteenth century and are they really hiding the treasure of the Temple of Jerusalem or the descendants of Jesus and Mary Magdalene? Is there an academic conspiracy to suppress the real evidence about technologically advanced human civilisations in the past? To read some people, you would certainly think so. After more than 25 years as a professional archaeologist (in the field, in academia and currently in a museum), I’ve never seen any of this evidence, so the conspiracy is obviously effective!

Is there is military/scientific conspiracy to hide the truth about alien contact, from the remains of the crashed saucer from Roswell to the manipulation of photographs showing ancient structures on Mars? None of the evidence stacks up, but that doesn’t stop people from explaining the lack of evidence as part of the effectiveness of the conspiracy.

Have the past two thousand years of European history seen every major event manipulated by a conspiracy to hide the truth about the origins of Christianity? Are we in the grip of an international Zionist/militant Islamist/New Word Order* (*delete as appropriate) conspiracy to rule the world? A study of the past, shorn of preconceptions about shadowy groups able to change the course of history, suggests that although humans can occasionally be whipped up with enthusiasm for causes of dubious value by demagogues, attempts at conspiracy have a habit of falling apart.

Nationalism and terrorism

It is easy to conclude that, ultimately, it doesn’t really matter what people believe about the past: it isn’t going to cause any harm. So what if some think that Stonehenge was built as a beacon for Pleiadean UFOs, that the Great Pyramid was built to plans concocted by refugees from Atlantis or that the world is less than ten thousand years old? These are eccentric or wrong beliefs, but no more harmful than believing in the efficacy of homeopathic medicine to cure minor ailments, that the Virgin Mary has chosen to manifest as a pattern in the window of a Chicago office or that consuming plenty of Vitamin C will help prevent you catching cold.

So why should we be bothered? Well, there is one area where muddle-headed beliefs about the past do have an impact on the present and one that can be positively dangerous: the co-option of the past to give expression to nationalistic or fundamentalist feelings, and to whip up people to an emotional pitch where they are prepared to commit outrages on other human being. We can see how the twentieth-century state of Israel was founded partly using beliefs derived from a book and how that belief conflicts with the equally strongly held beliefs of the Arab population of Palestine, deriving from a different (but similar) book. This is a cause for which people are willing to die horrible a death, from a bomb strapped to their midriff.

In conclusion…

The past is contested territory. That is a good thing, as it provokes debate and drives forward its exploration. It is not so contested, though, that it is a free-for-all for thousands of different interpretations. There are some things on which we can agree: there is no need to invoke the descent to earth of the Egyptian god Osiris to account for the development of agriculture, Octavian was the outright victor of the Battle of Actium, the stones of Avebury were put in place early in the third millennium BCE… Others are the subject of legitimate discussion: were the Bluestones of Stonehenge transported from South Wales by the builders of the monument or were they carried millennia earlier on a moving ice sheet? Was Tut‘ankhamūn the son or nephew of Akhnaten?

Things go wrong when people ask the wrong questions: does this hieroglyph depict a helicopter? No. How can this sixteenth-century map show Antarctica? It doesn’t. How can I find out if my house is built on a ley line? It isn’t. Why are there human and dinosaur tracks side by side? There aren’t.

We are the products of the human past, which is visible all around us. Even though we don’t often think about it, it is the past which guides our every action: we are constrained by habits and traditions, we live and work in places that have usually developed slowly over centuries, if not millennia. For this reason alone, the past is important. When you consider how the past can make us feel – the awe that standing in the King’s Chamber of the Great Pyramid inspires, the wonder of the rock-cut churches of Lalibela, the horror of World War II extermination camps – you can appreciate its power. Now think of how that power can be used to make us think and act in different ways. Do we want to allow people with sinister motives to use the past against us?

It is not just that the past can be misused to persuade people to commit atrocities: it can also be misused to prevent them from acting or to espouse causes for purely emotional reasons. If business interests want to deny the human element to current global warming and do nothing to stop it, then they need to produce robust data about the nature, scale and causes of past climate change and to take into account changes in humanity’s ability to affect the global environment; if anti-globalisation protesters want to turn the clock back to imagined small-scale societies with limited interaction, they need to show that societies of this sort one existed and how they functioned. Archaeology has a role to play in understanding current affairs at many levels and it is a role its practitioners have barely even begun to explore.

About KJF-M

Keith Fitzpatrick-Matthews was born a long time ago in Letchworth Garden City (Herts, England), where he grew up obsessed with archaeology, space travel and music. After failing to get a job in archaeology following graduation, he became a punk DJ in a Manchester nightclub. Then, in 1985, he got a job excavating in Baldock, just eight kilometers from where he was born. Moving to a new job in Chester in 1990, he worked in the city on various projects (including a Mesolithic rock-shelter in Carden Park, the first excavation of a slum courtyard in Britain in 1994, beginning new research into the Roman amphitheatre in 2000 and setting up the archaeology degree pathway at the University of Chester). He returned to North Hertfordshire in 2004, working (among other things) on helping to publish the sites on which he worked in the 1980s and researching the landscape of the parish in which he was born.

For some years now, he’s been running a website (www.badarchaeology.net) that tries to deal with the issues raised here, going into more detail about why particular ideas are wrong. He also has a blog (), dealing with more topical issues. The name Bad Archaeology was inspired by Phil Plait’s Bad Astronomy and Ben Goldacre’s Bad Science websites; Keith is not trying to position himself as an arbiter of ‘Good Archaeology’!