Perché mai Efesto (Vulcano) era deforme e brutto, tanto che la stessa madre Hera (Giunone) lo scaraventò via dall’Olimpo, relegandolo in un vulcano (l'Etna), che divenne la sua fucina? Perché non era bello e perfetto, Bombastico ed eccessivo, nei pregi e nei difetti anche del carattere, come tutti gli altri Dei dell'Olimpo? Perché era "quasi normale", tanto da distinguersi, da apparire come inferiore rispetto agli altri Dei?

Perché mai Efesto (Vulcano) era deforme e brutto, tanto che la stessa madre Hera (Giunone) lo scaraventò via dall’Olimpo, relegandolo in un vulcano (l'Etna), che divenne la sua fucina? Perché non era bello e perfetto, Bombastico ed eccessivo, nei pregi e nei difetti anche del carattere, come tutti gli altri Dei dell'Olimpo? Perché era "quasi normale", tanto da distinguersi, da apparire come inferiore rispetto agli altri Dei?

Quale malata fantasia religiosa – ci si è sempre chiesti – può produrre un Dio sgraziato e storpio, che conduce una vita rozza e possiede un lavoro tanto faticoso, certamente pericoloso e tanto umile, in esilio lontano dal Paradiso?

Gli antichi erano così 'poco svegli' da non comprendere che un mito deve essere creato almeno in qualche modo superiore all’uomo, figurarsi quindi un Dio?

Ebbene, un motivo c’è. Non pretendo che sia l'unico vero, né che sia totalmente sicuro, Pasuco, ma è un motivo ragionato e molto credibile e certamente anche affascinante...

Il mito si è andato a formare nell’Età del Bronzo, proprio quando il fabbro (professione che fu una filiazione di quella del vasaio, probabilmente*) con la sua attività, diventava man mano sempre più importante per la propria comunità, a fronte della sempre crescente richiesta di strumenti di metallo, sia per la vita quotidiana, sia per la difesa armata.

A differenza della pietra (selce) e del vetro vulcanico (ossidiana), che possono essere riaffilate solo un limitato numero di volte (e che si ottundono persino durante il trasporto, se non 'imballate' accuratamente, più probabilmente con pelli animali), la lega del bronzo è virtualmente immortale e gli strumenti possono essere rifusi e ridati a nuova vita, proprio e unicamente dal fabbro.

In più, in bronzo possono essere realizzati pugnali e spade, prima quasi impensabili con la pietra: strumenti che cambieranno i destini dell’uomo e modificheranno le tattiche di guerra per sempre.

Poco importa che il vetro vulcanico e persino la selce offrano strumenti più taglienti e più affilati: alla lunga, nelle sue varie forme, la lega del bronzo (più dura del semplice rame martellato), bellissima quasi quanto l’oro (non ci si deve lasciare ingannare dall’aspetto ossidato verdastro dei reperti archeologici!), si affermerà ovunque. Il vetro sarà comunque usato ancora a lungo (come in Sardegna l'ossidiana, o in sala operatoria le lame vitree per i microinterventi oculistici, ad esempio).

Il fabbro divenne così un personaggio essenziale, estremamente importante in ogni comunità, tanto da essere – quasi immancabilmente – sepolto con l’onore degli strumenti del suo lavoro unico ed importantissimo.

Fu eroicizzato, quindi divinizzato.

Ma – nella prima parte dell’Età del Bronzo – si lavorava prevalentemente il rame arsenicale (o bronzo d'arsenico, perché - di fatto - era già una lega e non un metallo puro), più facile a trovarsi perché più superficiale. Il fabbro, quindi, immancabilmente respirava i vapori d’arsenico e s’ammalava di quell’avvelenamento che oggi si chiama arseniosi cronica (da non confondersi con l'arseniosi acuta, altro capitolo interessantissimo, molto di moda nel rinascimento Italiano e tornato in auge tra gli Impressionisti).

I sintomi sono dovuti ad un blocco enzimatico della sostanza bianca e grigia del sistema nervoso, che (tra molti altri sintomi, tra cui meglio osservabili sono naturalmente quelli cutanei) conduce a sordità, zoppia e talvolta ad amputazione di parte degli arti…

Ecco, con ogni probabilità, perché Efesto nasce come un Dio appunto storpio e deforme, essendo egli la trasposizione nel mondo divino di un fabbro terreno così come lo si conosceva bene: già gli antichi avevano saputo riconoscere in quei sintomi la malattia professionale del fabbro!

E – ancora più stupefacente, ma del tutto credibile – avevano trovato la cura più adatta, nella prevenzione.

Ecco quindi spiegato un altro piccolo mistero: perché mai, verso la metà dell’Età del Bronzo, in tutto il Mediterraneo ci si sia orientati verso una lega – il 'bronzo di stagno' – molto più difficile a realizzarsi che non quella arsenicale, per via della rarità dello stagno.

Anche in questo caso ci si era a lungo interrogati circa perché mai gli uomini del Bronzo sembrassero così stupidi, prima di accorgersi (noi) che (loro) – faticosamente, certo, ma ineluttabilmente – imparavano i primi passi della metallurgia, cadevano, come un neonato che impari a camminare, ma si rialzavano testardi e riprovavano … E' il classico procedimento definito per 'tentativo ed errore' che l'umanità ha adottato in tutta la propria Storia.

Ecco, questo del Mito Divino è uno dei modi dell’uomo di raccontare la propria storia. E’ un metodo antico, semplice, che ricorre alla creazione del mito altisonante ed alla simbologia della metafora per raccontare i propri tentativi andati a male e le correzioni apposte, a differenza di quello che si farebbe adesso, pubblicando un lavoro scientifico, descrivendo Scopi, Materiali e Metodi ed elencando al termine le Conclusioni dedotte dopo averne ricontrollato la validità nella Discussione.

Non ti convince, Pasuco? Pazienza, se no. Ma io lo trovo credibile, oltre che affascinante. Per sicurezza, ti dò qualche altra info in nota°.

Che poi Efesto sia rappresentato come un uomo (perché il lavoro davanti ad un antica fornace era molto pesante e anche poco sano, esponendo a polmoniti e pleuriti, a parte l'arseniosi), non significa necessariamente che non ci siano state - nell'antichità - donne fabbro, proprio come ci sono anche adesso. Proprio recentemente ci si interroga su una tomba in cui è inumata una donna, con un corredo di strumenti tipici del fabbro...

In ogni caso, l’uomo dovrebbe conoscersi meglio, io credo, e ricordare la propria storia passata: chi non ha memoria dei propri errori, si sa, è destinato a ripeterli.

E quante volte ci siamo avvelenati da noi stessi, anche in tempi recenti, esattamente come il fabbro dell’Età del Bronzo?

* Il vasaio usava il forno. Probabilmente, sperimentando nuove possibilità di colori, mise a 'cuocere' campioni conteneti metalli ed osservò la prima fusione. Il forno del vasaio possiede tutti gli elementi (alte temperature, mancanza di ossigeno etc) per produrre la fusione dei metalli. La nozione comune di una prima fusione accidentale in un fuoco da campo è da considerarsi favolistica, in quanto non raggiunge mai le medesime condizioni.

° Tieni presente, Pasuco, che i sintomi dell'arseniosi cronica descritta oggi non sono più quelli che erano osservabili allora: oggi infatti si tratta prevalentemente di ingestione (più spesso con l'acqua, più di rado con gli alimenti), talvolta di assorbimento transcutaneo (come accadde per il 'Liquido di Fowler'). Allora, invece, si trattava di respirazione diretta dell'arsenico, il che fa una discretamente grande differenza.

I. Chronic Adverse Effects

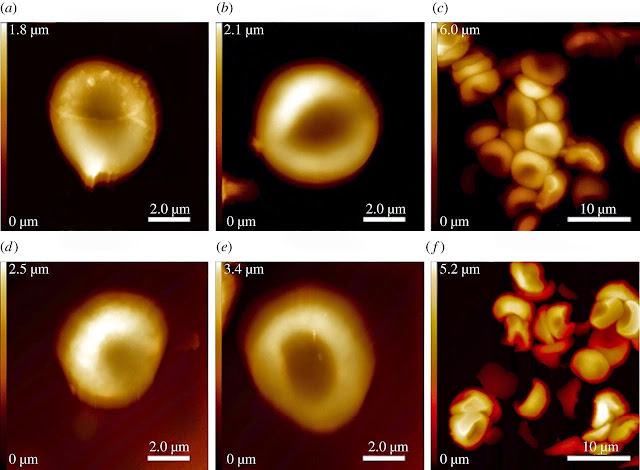

After a few years of continued low level of arsenic exposure, many skin ailments appear, i.e. Hypopigmentation (white spots), Hyperpigmentation (dark spots), collectively called Melanosis by some physicians and dyspigmentaion by others. Also keratosis (break up of the skin on hands and feet). We have assembled a collection of photographs of patients with typical symptoms. We have plots of incidence of these ailments versus integrated dose and versus maximum dose for three villages in Inner Mongolia. These suggest lineraity of incidence with dose above a possible threshold at 75 ppb in the water, with incidence rising to approach 100% near 1000 ppb. In developed countries dyspigmentation and even keratosises do not always lead to death. But in Bangladesh (as in ancient times), a farmer with keratoses on his feet may continue to walk upon them and develop gangrene. Then his foot must be amputated and he can no longer work and feed his family. So far several thousand cases of melanosis have been identified in Bangladesh but it is important to note that as of July 2005 only about 30% of the villages have been surveyed. More information from greater number of surveys may show a much greater number of people affected.

After a latency of about 10 years, skin cancers appear. After a latency of 20 - 30 years, internal cancers - particularly bladder and lung appear.These have all been seen in Taiwan and in Chile. The data from Taiwan and Chile suggest that biggest risk of death is from internal cancers. The data from Chile suggests that 30 years after a 5-year exposure of drinking water at a concentration of 0.5 ppm (and reduced exposure thereafter) will result in a cancer risk of 10%. No one knows how to extrapolate to the lower exposure of 0.05 ppm (50 ppb or 50 micrograms per liter), but if one takes a "default" linear response, the risk is 1%. At the WHO guideline of 10 ppb, to be effective in the USA about 2006, the risk is still 0.2%.

Arsenic absorption is also believed to lead to vascular disease.

Chemistry