L'articolo è preso dal Dieneke's Anthropology blog ed è un nuovissimo lavoro di S. Leslie et Al, di cui un riassunto è comparso su Nature, ma del quale i dettagli scientifici non sono ancora aperti al pubblico.

I punti rilevanti - in esso - sono numerosi ed interessanti.

1) Gli 'Inglesi' ne escono come una popolazione piuttosto omogenea (malgrado il gran parlare che si è fatto di 'popolazione composita' e l'apparente situazione di contrapposizione tra le 'varie etnie', che in qualche caso si sono anche fronteggiate in modo sanguinoso).

2) Gli autori hanno identificato 17 clusters differenti di 'Inglesi', che possiedono prevalentemente una distribuzione geografica (cioé si sono espansi in un'unica area dell'isola), pur esistendo alcuni clusters che eludono questa regola ed hanno una diffusione più frammentaria ed irregolare.

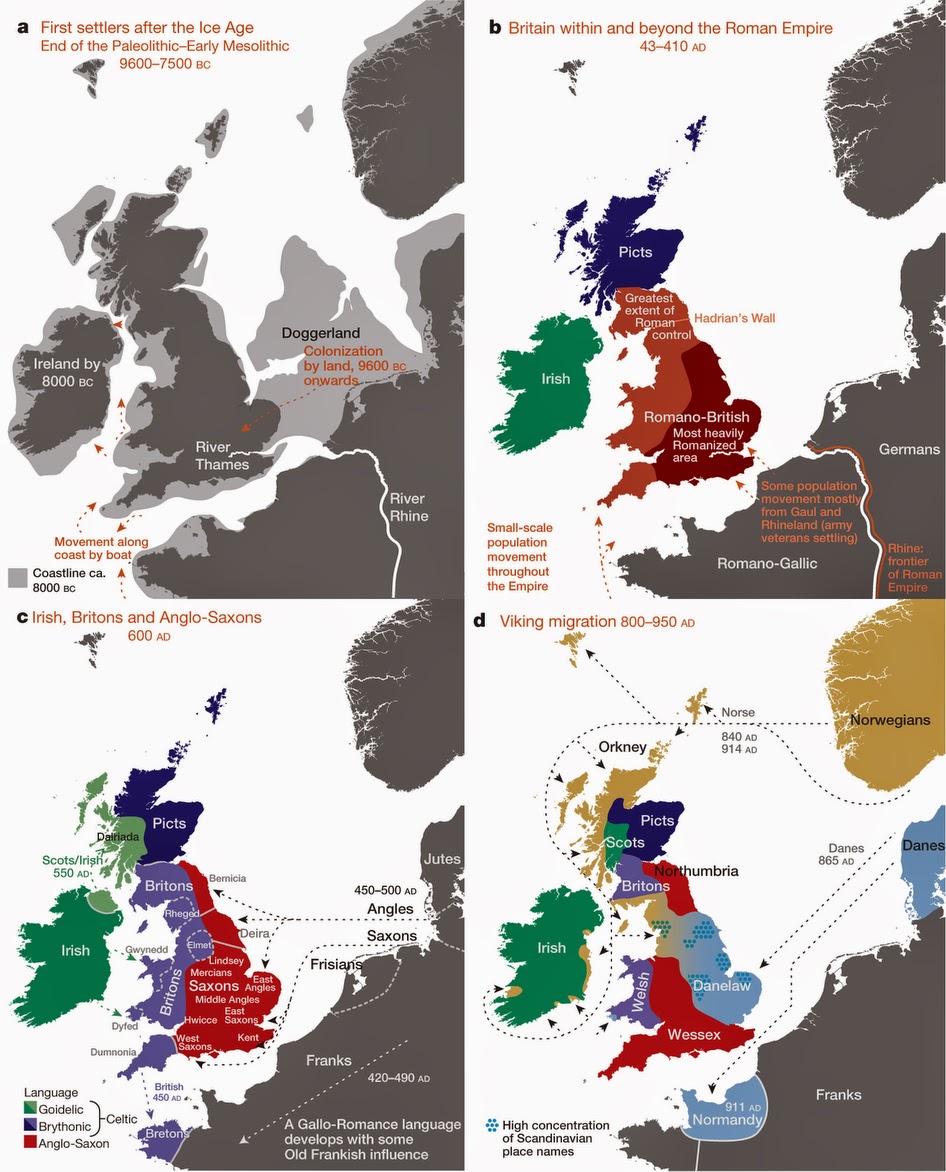

3) Il confronto tra cluster inglesi e clusters continentali europei, ha permesso di concludere che quelli più diffusamente distribuiti sono con ogni probabilità i più antichi, mentre gli altri debbano essere più recenti (gli autori fanno l'esempio delle Orcadi, che sono rappresentati fortemente da un paio di clusters Norvegesi e rappresenterebbero la presenza Vichinga).

4) La sostituzione di popolazione (una mistura di locali e Romani), che avvenne con l'ingresso dei Sassoni è stata quantificata in una percentuale molto più bassa di quella prima ritenuta corretta: sarebbe contenuta - a seconda delle zone - tra il 10% ed il 40%. Pertanto la consistente modifica, che pure avvenne, in termini di lingua parlata, tipi di agricoltura e ceramiche, antroponimi, toponimi e fitonimi, non permette comunque d'ipotizzare una più consistente entità percentuale di sostituzione (sempre e comunque molto al di sotto del 50%).

5) La molto decantata occupazione Danese Vichinga non ha lasciato altro che minime tracce di popolazione: l'apporto in termini di 'pool genetico' di popolazione (DNA) è estremamente basso e - per le isole Orcadi, che rappresentano i picchi massimi - l'apporto riscontrato non supera un minoritario 25% percentuale di partecipazione Norvegese.

6) Come già sostenuto da altri studi, anche questa ricerca dimostra l'inesistenza dei Celti come popolazione a sé stante. 'Celti' semplicemente risulterebbero quei gruppi di popolazione ove non compaiono i Sassoni, ma non per appartenenza a questo o quel gruppo particolare. Un discorso a parte meritano i Gallesi, che corrisponderebbero effettivamente meglio ai primi immigrati del periodo post-glaciale.

Tralascio di elencare tutte le possibili similitudini con la Sardegna. Mi limito a sottolineare solamente che per molto tempo (ed ancora adesso) si è ipotizzata la Malaria come fattore limitante di una maggiore presenza genetica 'estranea' in Sardegna. Si vede bene che non si tratta di un fattore assolutamente necessario: probabilmente basta l'ostacolo geografico/biologico proposto anche qui da un pur breve tratto di mare. Anche in questo caso, gli studi puramente 'linguistici' non sono confermati dai dati biologici della Genetica di Popolazioni.

British origins (Leslie et al. 2015)

The long-awaited paper on the People of the British Isles has just appeared in Nature. I will update this entry with more information.

UPDATE:

The authors write:

Most of the clusters are geographical, but some span different regions (e.g., the "yellow circle" cluster). The elephant in the room is the "red square" cluster which spans Central/South England. The authors write:

The authors draw conclusions on several historical episodes of British history. The big one is the extent of Anglo-Saxon ancestry:

Nature 519, 309–314 (19 March 2015) doi:10.1038/nature14230

The fine-scale genetic structure of the British population

Stephen Leslie et al.

Fine-scale genetic variation between human populations is interesting as a signature of historical demographic events and because of its potential for confounding disease studies. We use haplotype-based statistical methods to analyse genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) data from a carefully chosen geographically diverse sample of 2,039 individuals from the United Kingdom. This reveals a rich and detailed pattern of genetic differentiation with remarkable concordance between genetic clusters and geography. The regional genetic differentiation and differing patterns of shared ancestry with 6,209 individuals from across Europe carry clear signals of historical demographic events. We estimate the genetic contribution to southeastern England from Anglo-Saxon migrations to be under half, and identify the regions not carrying genetic material from these migrations. We suggest significant pre-Roman but post-Mesolithic movement into southeastern England from continental Europe, and show that in non-Saxon parts of the United Kingdom, there exist genetically differentiated subgroups rather than a general ‘Celtic’ population.

Link

Many people in the UK feel a strong sense of regional identity, and it now appears that there may be a scientific basis to this feeling, according to a landmark new study into the genetic makeup of the British Isles. An international team, led by researchers from the University of Oxford, UCL (University College London) and the Murdoch Childrens Research Institute in Australia, used DNA samples collected from more than 2,000 people to create the first fine-scale genetic map of any country in the world. Their findings, published in Nature, show that prior to the mass migrations of the 20th century there was a striking pattern of rich but subtle genetic variation across the UK, with distinct groups of genetically similar individuals clustered together geographically. By comparing this information with DNA samples from over 6,000 Europeans, the team was also able to identify clear traces of the population movements into the UK over the past 10,000 years. Their work confirmed, and in many cases shed further light on, known historical migration patterns. Key findings There was not a single "Celtic" genetic group. In fact the Celtic parts of the UK (Scotland, Northern Ireland, Wales and Cornwall) are among the most different from each other genetically. For example, the Cornish are much more similar genetically to other English groups than they are to the Welsh or the Scots. There are separate genetic groups in Cornwall and Devon, with a division almost exactly along the modern county boundary. The majority of eastern, central and southern England is made up of a single, relatively homogeneous, genetic group with a significant DNA contribution from Anglo-Saxon migrations (10-40% of total ancestry). This settles a historical controversy in showing that the Anglo-Saxons intermarried with, rather than replaced, the existing populations. The population in Orkney emerged as the most genetically distinct, with 25% of DNA coming from Norwegian ancestors. This shows clearly that the Norse Viking invasion (9th century) did not simply replace the indigenous Orkney population. The Welsh appear more similar to the earliest settlers of Britain after the last ice age than do other people in the UK. There is no obvious genetic signature of the Danish Vikings, who controlled large parts of England ("The Danelaw") from the 9th century. There is genetic evidence of the effect of the Landsker line -- the boundary between English-speaking people in south-west Pembrokeshire (sometimes known as "Little England beyond Wales") and the Welsh speakers in the rest of Wales, which persisted for almost a millennium. The analyses suggest there was a substantial migration across the channel after the original post-ice-age settlers, but before Roman times. DNA from these migrants spread across England, Scotland, and Northern Ireland, but had little impact in Wales. Many of the genetic clusters show similar locations to the tribal groupings and kingdoms around end of the 6th century, after the settlement of the Anglo-Saxons, suggesting these tribes and kingdoms may have maintained a regional identity for many centuries. The Wellcome Trust-funded People of the British Isles study analysed the DNA of 2,039 people from rural areas of the UK, whose four grandparents were all born within 80km of each other. Because a quarter of our genome comes from each of our grandparents, the researchers were effectively sampling DNA from these ancestors, allowing a snapshot of UK genetics in the late 19th Century. They also analysed data from 6,209 individuals from 10 (modern) European countries. To uncover the extremely subtle genetic differences among these individuals the researchers used cutting-edge statistical techniques, developed by four of the team members. They applied these methods, called fineSTRUCTURE and GLOBETROTTER, to analyse DNA differences at over 500,000 positions within the genome. They then separated the samples into genetically similar individuals, without knowing where in the UK the samples came from. By plotting each person onto a map of the British Isles, using the centre point of their grandparents' birth places, they were able to see how this distribution correlated with their genetic groupings. The researchers were then able to "zoom in" to examine the genetic patterns in the UK at levels of increasing resolution. At the broadest scale, the population in Orkney (islands to the north of Scotland) emerged as the most genetically distinct. At the next level, Wales forms a distinct genetic group, followed by a further division between north and south Wales. Then the north of England, Scotland, and Northern Ireland collectively separate from southern England, before Cornwall forms a separate cluster. Scotland and Northern Ireland then separate from northern England. The study eventually focused at the level where the UK was divided into 17 genetically distinct clusters of people. Dr Michael Dunn, Head of Genetics & Molecular Sciences at the Wellcome Trust, said: "These researchers have been able to use modern genetic techniques to provide answers to the centuries' old question -- where we come from. Beyond the fascinating insights into our history, this information could prove very useful from a health perspective, as building a picture of population genetics at this scale may in future help us to design better genetic studies to investigate disease."

UPDATE:

The authors write:

Consistent with earlier studies of the UK, population structure within the PoBI collection is very limited. The average of the pairwise FST estimates between each of the 30 sample collection districts is 0.0007, with a maximum of 0.003 (Supplementary Table 1).These are extremely small differences in the European (let alone global) context. So, the British are, overall, a very homogeneous population. This is what led the researchers to use methods such as ChromoPainter/ fineStructure/ Globetrotter that can squeeze out fine-scale population structure by exploiting linkage disequilibrium. Thus, the authors are able to detect 17 main clusters of the British.

Most of the clusters are geographical, but some span different regions (e.g., the "yellow circle" cluster). The elephant in the room is the "red square" cluster which spans Central/South England. The authors write:

There is a single large cluster (red squares) that covers most of central and southern England and extends up the east coast. Notably, even at the finest level of differentiation returned by fineSTRUCTURE (53 clusters), this cluster remains largely intact and contains almost half the individuals (1,006) in our study.The authors then tried to infer the ancestry of the British clusters in terms of continental European clusters, which is to be published separately. In the plot on the right, you see the British clusters (columns) and their continental European sources (rows). The authors observe that clusters that are widely represented in Britain are likely to be older, while those that are missing in some populations are likely to be younger, because they didn't have the chance to spread across Britain. For example, a couple of Norwegian clusters are strongly represented in the Orkney islands, and these are likely to reflect Viking colonization.

The authors draw conclusions on several historical episodes of British history. The big one is the extent of Anglo-Saxon ancestry:

After the Saxon migrations, the language, place names, cereal crops and pottery styles all changed from that of the existing (Romano-British) population to those of the Saxon migrants. There has been ongoing historical and archaeological controversy about the extent to which the Saxons replaced the existing Romano-British populations. Earlier genetic analyses, based on limited samples and specific loci, gave conflicting results. With genome-wide data we can resolve this debate. Two separate analyses (ancestry profiles and GLOBETROTTER) show clear evidence in modern England of the Saxon migration, but each limits the proportion of Saxon ancestry, clearly excluding the possibility of long-term Saxon replacement. We estimate the proportion of Saxon ancestry in Cent./S England as very likely to be under 50%, and most likely in the range of 10–40%.Two other details are the lack of Danish Viking ancestry in England:

In particular, we see no clear genetic evidence of the Danish Viking occupation and control of a large part of England, either in separate UK clusters in that region, or in estimated ancestry profiles, suggesting a relatively limited input of DNA from the Danish Vikings and subsequent mixing with nearby regions, and clear evidence for only a minority Norse contribution (about 25%) to the current Orkney population.And, the absence of a unified pre-Saxon "Celtic" population. What seems to unify "Celts" is lower levels/absence of the Saxon influence, rather than belonging to a homogeneous "Celtic" population:

We saw no evidence of a general ‘Celtic’ population in non-Saxon parts of the UK. Instead there were many distinct genetic clusters in these regions, some amongst the most different in our study, in the sense of being most separated in the hierarchical clustering tree in Fig. 1. Further, the ancestry profile of Cornwall (perhaps expected to resemble other Celtic clusters) is quite different from that of the Welsh clusters, and much closer to that of Devon, and Cent./S England. However, the data do suggest that the Welsh clusters represent populations that are more similar to the early post-Ice-Age settlers of Britain than those from elsewhere in the UK.Unfortunately, the authors have decided not to make their data publicly available. This is very unfortunate, and will keep this research out of the hands of many people who would be interested in it and who would be interested in analyzing this data. I can already guess the disappointment of people of British ancestry from around the world who have a genealogical interest in tracing their British ancestors to particular areas of the UK. Apparently, the data is deposited in the EGA archive, access requires red tape, and is apparently limited to institutional researchers. Thus, this data, perhaps the richest genetic survey of any country to date, will not be fully utilized to further science.

Nature 519, 309–314 (19 March 2015) doi:10.1038/nature14230

The fine-scale genetic structure of the British population

Stephen Leslie et al.

Fine-scale genetic variation between human populations is interesting as a signature of historical demographic events and because of its potential for confounding disease studies. We use haplotype-based statistical methods to analyse genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) data from a carefully chosen geographically diverse sample of 2,039 individuals from the United Kingdom. This reveals a rich and detailed pattern of genetic differentiation with remarkable concordance between genetic clusters and geography. The regional genetic differentiation and differing patterns of shared ancestry with 6,209 individuals from across Europe carry clear signals of historical demographic events. We estimate the genetic contribution to southeastern England from Anglo-Saxon migrations to be under half, and identify the regions not carrying genetic material from these migrations. We suggest significant pre-Roman but post-Mesolithic movement into southeastern England from continental Europe, and show that in non-Saxon parts of the United Kingdom, there exist genetically differentiated subgroups rather than a general ‘Celtic’ population.

Link

Many people in the UK feel a strong sense of regional identity, and it now appears that there may be a scientific basis to this feeling, according to a landmark new study into the genetic makeup of the British Isles. An international team, led by researchers from the University of Oxford, UCL (University College London) and the Murdoch Childrens Research Institute in Australia, used DNA samples collected from more than 2,000 people to create the first fine-scale genetic map of any country in the world. Their findings, published in Nature, show that prior to the mass migrations of the 20th century there was a striking pattern of rich but subtle genetic variation across the UK, with distinct groups of genetically similar individuals clustered together geographically. By comparing this information with DNA samples from over 6,000 Europeans, the team was also able to identify clear traces of the population movements into the UK over the past 10,000 years. Their work confirmed, and in many cases shed further light on, known historical migration patterns. Key findings There was not a single "Celtic" genetic group. In fact the Celtic parts of the UK (Scotland, Northern Ireland, Wales and Cornwall) are among the most different from each other genetically. For example, the Cornish are much more similar genetically to other English groups than they are to the Welsh or the Scots. There are separate genetic groups in Cornwall and Devon, with a division almost exactly along the modern county boundary. The majority of eastern, central and southern England is made up of a single, relatively homogeneous, genetic group with a significant DNA contribution from Anglo-Saxon migrations (10-40% of total ancestry). This settles a historical controversy in showing that the Anglo-Saxons intermarried with, rather than replaced, the existing populations. The population in Orkney emerged as the most genetically distinct, with 25% of DNA coming from Norwegian ancestors. This shows clearly that the Norse Viking invasion (9th century) did not simply replace the indigenous Orkney population. The Welsh appear more similar to the earliest settlers of Britain after the last ice age than do other people in the UK. There is no obvious genetic signature of the Danish Vikings, who controlled large parts of England ("The Danelaw") from the 9th century. There is genetic evidence of the effect of the Landsker line -- the boundary between English-speaking people in south-west Pembrokeshire (sometimes known as "Little England beyond Wales") and the Welsh speakers in the rest of Wales, which persisted for almost a millennium. The analyses suggest there was a substantial migration across the channel after the original post-ice-age settlers, but before Roman times. DNA from these migrants spread across England, Scotland, and Northern Ireland, but had little impact in Wales. Many of the genetic clusters show similar locations to the tribal groupings and kingdoms around end of the 6th century, after the settlement of the Anglo-Saxons, suggesting these tribes and kingdoms may have maintained a regional identity for many centuries. The Wellcome Trust-funded People of the British Isles study analysed the DNA of 2,039 people from rural areas of the UK, whose four grandparents were all born within 80km of each other. Because a quarter of our genome comes from each of our grandparents, the researchers were effectively sampling DNA from these ancestors, allowing a snapshot of UK genetics in the late 19th Century. They also analysed data from 6,209 individuals from 10 (modern) European countries. To uncover the extremely subtle genetic differences among these individuals the researchers used cutting-edge statistical techniques, developed by four of the team members. They applied these methods, called fineSTRUCTURE and GLOBETROTTER, to analyse DNA differences at over 500,000 positions within the genome. They then separated the samples into genetically similar individuals, without knowing where in the UK the samples came from. By plotting each person onto a map of the British Isles, using the centre point of their grandparents' birth places, they were able to see how this distribution correlated with their genetic groupings. The researchers were then able to "zoom in" to examine the genetic patterns in the UK at levels of increasing resolution. At the broadest scale, the population in Orkney (islands to the north of Scotland) emerged as the most genetically distinct. At the next level, Wales forms a distinct genetic group, followed by a further division between north and south Wales. Then the north of England, Scotland, and Northern Ireland collectively separate from southern England, before Cornwall forms a separate cluster. Scotland and Northern Ireland then separate from northern England. The study eventually focused at the level where the UK was divided into 17 genetically distinct clusters of people. Dr Michael Dunn, Head of Genetics & Molecular Sciences at the Wellcome Trust, said: "These researchers have been able to use modern genetic techniques to provide answers to the centuries' old question -- where we come from. Beyond the fascinating insights into our history, this information could prove very useful from a health perspective, as building a picture of population genetics at this scale may in future help us to design better genetic studies to investigate disease."