possibile spiegazione per la scomparsa del Neanderthal. I

ricercatori avvertono però che una grande eruzione in

Italia (responsabile di un raffreddamento climatico

globale) avrebbe più probabilmente solo dato un colpo di

grazia ad una specie già in serio pericolo biologico

d'estinzione per la propria scarsità numerica (un 'collo di

bottiglia') e che già stava soccombendo alla più

competitiva specie cui l'uomo moderno appartiene...

D'altro canto, sembrerebbe strano che una temperatura più

rigida - da sola - potesse mettere in difficoltà proprio il

Neanderthal, che per le temperature fredde era

attrezzatissimo.

Lo studio entra nei risvolti quantitativi e nell'estensione

geografica della diminuzione di temperatura. Sembra che

l'entità della diminuzione fosse - in Europa Occidentale -

solo di 2/4 gradi e che quindi la maggiore differenza di

temperatura (con le maggiori difficoltà ambientali) abbia

'bipassato' proprio le zone in cui i Neanderthal resistettero

più a lungo. Le zone geografiche più colpite sarebbero state

l'Asia e l'Europa Orientale.

Quindi, sostanzialmente, lo studio è negativo: la

conclusione è che non fu l'abbassamento di temperatura ad

eliminare il Neanderthal. Ma i ricercatori ritengono di

avere sottolineato ancora una volta quanto sia sempre

stato determinante il clima per tutti gli esseri viventi ed in

quale misura l'uomo anatomicamente si sia sempre

dimostrato più adattabile del Neanderthal alle variazioni

ambientali.

Did a volcanic cataclysm

40,000 years ago trigger the

final demise of the Neanderthals?

The Campanian Ignimbrite (CI) eruption in Italy 40,000 years ago was one of the largest volcanic cataclysms in Europe and injected a significant amount of sulfur-dioxide (SO2) into the stratosphere.

Scientists have long debated whether this eruption contributed to the final extinction of the Neanderthals.

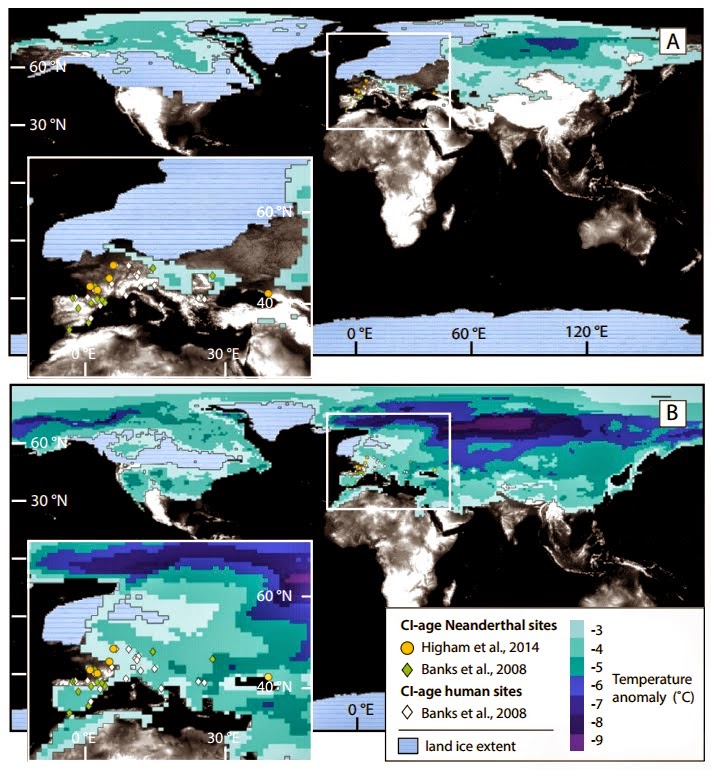

This new study by Benjamin A. Black and colleagues tests this hypothesis with a sophisticated climate model. Figure 4 in B.A. Black et al.: This image shows annually averaged temperature anomalies in excess of 3°C for the first year after the Campanian Ignimbrite (CI) eruption compared with spatial distribution of hominin sites with radiocarbon ages close to that of the eruption

[Credit: B.A. Black et al. and the journal Geology]

Black and colleagues write that the CI eruption approximately coincided with the final decline of Neanderthals as well as with dramatic territorial and cultural advances among anatomically modern humans.

Because of this, the roles of climate, hominin competition, and volcanic sulfur cooling and acid deposition have been vigorously debated as causes of Neanderthal extinction.

They point out, however, that the decline of Neanderthals in Europe began well before the CI eruption: "Radiocarbon dating has shown that at the time of the CI eruption, anatomically modern humans had already arrived in Europe, and the range of Neanderthals had steadily diminished.

Work at five sites in the Mediterranean indicates that anatomically modern humans were established in these locations by then as well."

"While the precise implications of the CI eruption for cultures and livelihoods are best understood in the context of archaeological data sets," write Black and colleagues, the results of their study quantitatively describe the magnitude and distribution of the volcanic cooling and acid deposition that ancient hominin communities experienced coincident with the final decline of the Neanderthals.

In their climate simulations, Black and colleagues found that the largest temperature decreases after the eruption occurred in Eastern Europe and Asia and sidestepped the areas where the final Neanderthal populations were living (Western Europe).

Therefore, the authors conclude that the eruption was probably insufficient to trigger Neanderthal extinction.

However, the abrupt cold spell that followed the eruption would still have significantly impacted day-to-day life for Neanderthals and early humans in Europe.

Black and colleagues point out that temperatures in Western Europe would have decreased by an average of 2 to 4 degrees Celsius during the year following the eruption.

These unusual conditions, they write, may have directly influenced survival and day-to-day life for Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans alike, and emphasize the resilience of anatomically modern humans in the face of abrupt and adverse changes in the environment.

Source: Geological Society of America [March 20, 2015]