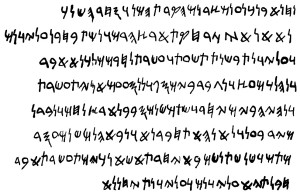

The Paraíba Inscription

While the Kensington Runestone undoubtedly exists, the same cannot be said for the so-called Paraíba (or Parahyba) Inscription, for which the sole evidence is a transcription accompanying a letter sent to Cândido José de Araújo Viana (1793-1875), the Visconde (later Marqués) de Sapucahy, President of the Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasiliero in Rio de Janeiro (Brazil) in 1872, who passed it to Ladislau de Souza Mello Netto

(1838-94). Although Netto was a botanist, he was also the interim

director of the Museum Nacional and had a knowledge of Punic archaeology

and the Hebrew language. The following year, the discovery was reported

by the newly formed London Anthropological Society in Anthropologia (1, 208) in a letter sent by A F Jones from Rio de Janeiro, who said that “[t]he published accounts of this find are so vague and unscientific that I can form no opinion of my own about it”.

At a meeting of the Society on 6 January 1874, three translations were

compared and there was considerable discussion about its authenticity;

on the 11 August 1874, A F Jones wrote again to the Society, saying that

Ernest Renan (1823-1892), the Semiticist, considered it a hoax. Other experts in Semitic languages, including Konstantin Schlottmann (1819-1887) and Julius Euting (1839-1913) were also of the opinion that the supposed inscription was a fake.

In the meantime, Netto had tried to

locate the original inscription. The letter writer was one Joaquim Alves

da Costa, a plantation owner from a place named Pouso Alto, near

Paraíba; several places called Pouso Alto were found, while two places

named Paraíba are known (one in the province of the same name, the other

near Rio de Janeiro). Alves da Costa and his estate proved impossible

to locate and Netto concluded that the whole affair was nothing more

than a hoax, publishing a report as Lettre

à Monsieur Ernest Renan à propos de l’Inscription Phénicienne Apocryphe

soumise en 1872 à l’Institut historique, géographiqe et ethnographique

du Brésil (“Letter to M Ernest Renan concerning the fake

Phoenician inscription submitted in 1872 to the Historical, Geographical

and Ethnographic Institute of Brazil”) in 1885. Netto blamed the hoax

on foreigners who were trying to discredit Brazilian scientists and

although he claimed to know the identity of the hoaxer, declined to

reveal it.

However, the story was revived more than

eighty years after Netto’s debunking work was published in 1885, when

Jules Piccus (1920-1997), professor of Romance languages at the

University of Massachusetts (Amherst, USA), bought a scrapbook at a

jumble sale in Providence (Rhode Island, USA) in 1967. It contained

correspondence sent by Netto to Wilberforce Eames

(1855-1937), a librarian at New York Public Library, which included a

copy of the alleged inscription and a translation made by Netto in 1874.

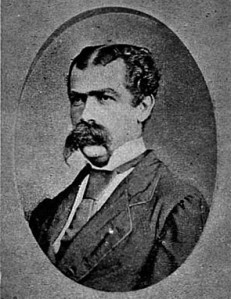

Piccus, who seems to have been unaware of Netto’s 1885 report, sent a

copy to Cyrus Herzl Gordon

(1909-2001), head of the Department of Mediterranean Studies at

Brandeis University in Waltham (Massachusetts, USA) and an expert in

ancient Semitic languages. Unlike Renan, he thought the Paraíba

inscription contained elements of Phoenician style that were unknown in

the nineteenth century and concluded that it was genuine.

Gordon was quick to release the story to the media, with a report appearing in The New York Times by the science writer Walter Seager Sullivan (1918-1996) that was widely syndicated to other newspapers, and a sensational report by A Douglas Matthews in Life.

This is a tactic widely used by pseudoscientists and regarded with

suspicion by scholars. Despite Gordon’s certainty about the genuineness

of the inscription, he failed to find support from other linguists. He

conducted a long and acrimonious dispute with Frank Moore Cross Jr

(born 1921), Hancock Professor of Hebrew and Other Oriental Languages

Emeritus at Harvard. Cross was scathing in his criticisms of Gordon,

pointing to problems with the script, vocabulary and spelling. Gordon

continued to champion this text and others as evidence for numerous

transaltantic contacts in Antiquity but failed to convince sceptics.

Like the Kensington Runestone, the

Paraíba Inscription was quickly denounced by linguists, subsequently to

be revived by those claiming that its peculiarities could be explained

by more recent discoveries that would have been unknown to a

nineteenth-century hoaxer. Unlike the Runestone, though, there is no

artefact to examine, no physical evidence and not even an accepted

findspot. It has all the hallmarks of a crude fraud.

Si direbbe che i falsari abbiano imparato molto anch'essi da questo episodio. L'esclusione dalla considerazione scientifica di ciò che non è prodotto in originale all'osservazione sembra essere l'unica efficace difesa.

Se Parahibo ha così tanto in comune con Tzricottu, Gordon con chi si potrebbe accomunare, amico mio?

So che hai in mente qualche nome: è solo questione di Tempo.