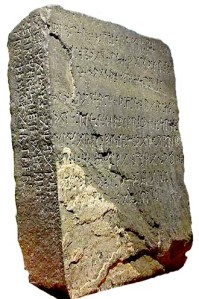

The Kensington Runestone

In 1942, Matthew Stirling, Director of the American Bureau of Ethnology, described this stone, unearthed in Minnesota in 1898 as “probably the most important archaeological object yet found in North America”.

It appears to relate a story of exploration deep into the heart of the

continent by a party of Swedes and Norwegians in 1362; if genuine, it

would certainly deserve Stirling’s fulsome praise. Although the stone

still has its supporters, especially in the area where it was found, the

opinion of the majority of scholars since 1950 has been that the

inscription is a crude fraud. How did it go from being regarded as one

of the greatest discoveries of North American archaeology to something

tainted with fraudulent origins in so short a time?

Considerable doubt exists surrounding

the circumstances of discovery, which has been exploited by sceptics,

but it is likely that it was unearthed by Olof Ohman,

a farmer of Swedish origin, on his farm in rural Minnesota in November

1898 (doubts exist about the precise date and accusations have been made

that the inscription was made after the slab was uncovered). Ohman was

clearing poplar trees from a hillock in the swamps to the

north-north-east of Kensington on land that he had owned since 1890.

Although there was initial excitement at the discovery, the stone faded

into brief obscurity after scholars expressed their scepticism about it.

In the meantime, Ohman seems to have forgotten about it and the stone

was used as a step.

In 1907, the social historian Hjalmar Rued Holand

(1872-1963) ‘rediscovered’ the stone. He allegedly started out as a

sceptic but was quickly convinced by the authenticity of the inscription

and spent the remainder of his long life trying to win it mainstream

acceptance. The high point came when the stone was exhibited at the

Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum in 1949, and although the

Institution was careful to avoid endorsing it as a genuine Viking

artefact, its supporters see its temporary exhibition in the capital of

the USA as evidence that scholars were treating it seriously.

Nevertheless, the linguistic peculiarities of the inscription have dogged it since it was first examined by Olaus Breda

(1853-1916) in 1899. He pointed to its strange mixture of Swedish and

Norwegian forms, its apparent inclusion of English words and its use of a

word not attested before the nineteenth century, opdægelse, to

mean “voyage of discovery”. Supporters have claimed that advances in

scholarship since 1899 have shown these peculiarities to be normal for

the fourteenth century. While this is true to a limited extent, it is

also over-stating the case: the mixture of languages still needs to be

explained away, while there is still that niggling opdægelse.

This is not to mention the lack of case endings: fourteenth-century

Norse nouns were still declined, but not one is on the Runsetone. Then

there are the numerals. Although they are claimed to be types found on primstave, runic calendar sticks, they are not: they are a form not attested before the nineteenth century, when they were used in Swedish folk contexts.

There is the very odd coincidence that

the inscription claims that ten Norse explorers were killed by Native

Americans in Minnesota in 1362, while ten Scandinavian settlers were killed by Native Americans in Minnesota exactly five hundred years later,

in 1862. This is odd, but not conclusive evidence for fraud. The

biggest problem is in explaining what Scandinavians were doing in the

middle of the North American continent in the middle of the fourteenth

century. This was a period when the Norse settlements in Greenland were

in decline, when contact with the Norwegian homeland was sporadic and

failing. Moreover, it was a period when voyages of exploration were at

an end. Hjalmar Holand was forced to construct an elaborate (and

implausible) scenario for the presence of Scandinavians in Minnesota

that ignores their known mode of coastal exploration. No archaeological

evidence for these explorers has been found beyond a series of claimed

“anchor stones” (anche questo giunge nuovo!) said to mark mooring spots. We are not given details of

the distribution of these stones or accurate drawings of different

types; instead, we are asked to accept on trust that they resemble

similar stones found in Norway. The problem with these stones is that

the holes were not chiselled (the standard practice in Norway) but were

drilled, using the one-inch (25.4 mm) bit that was standard for blasting

operations in the nineteenth-century USA.