Jerry Vardaman’s “microletters” on Roman coins

This is an odd one, and it’s

something that seems to have passed by the notice of most “alternative”

archaeologists. It concerns some claims made by a genuine academic

archaeologist that relate to coinage of the late first century BCE and

early first century CE, which he believed demonstrated that the

chronology of the career of Jesus of Nazareth have been dated wrongly.

These matters of chronology are not the focus of interest here (indeed,

they are abstruse and relate more to biblical exegesis and religious

history than to archaeology as such): it is the claim that coins minted

in the eastern (predominantly Greek speaking) part of the Roman Empire

contain what are claimed to be “microletters”. These are microscopic

letters that are alleged to have been created on the coin dies by the

moneyers who struck them. It is an unusual claim, but coming from an

academic archaeologist, ought to be examined carefully. After all,

academics never make mistakes, do they?

The discoverer of the “microletters” was Ephraim Jeremiah (‘Jerry’) Vardaman (1927-2000), a lecturer in archaeology and religion at Mississippi State University in Starkville (Mississippi, USA), where he was the founder and director of the Cobb Institute of Archaeology from 1973 to 1981, and from which he retired in 1992. He had previously been a Baptist Bible chair teacher at Tarleton State College (now University), an adjunct teacher of Old Testament at The Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary from 1956 to 1958 and assistant professor and associate professor of New Testament archaeology at The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary (Louisville, Kentucky, USA) from 1958 to 1972. He also taught at the Hong Kong Baptist Seminary,

perhaps after his retirement from Mississippi State University; he was

certainly leading seminars there in 1998. His bachelor’s degree was

awarded by Southwestern Seminary and he obtained two doctorates, one

from the Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in 1957 (on Hermeticism and the Fourth Gospel) and the other from Baylor University in 1974 (on The Inscriptions of King Herod I). He undertook postdoctoral work at both the University of Oxford (UK) and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem

(Israel). He excavated extensively in the Middle East, at the sites of

Bethel, Shechem, Ramat Rachel, Caesarea, Ashdod, Macherus and Elusa. All

in all, this is an impressive curriculum vitae and one that means we should take Dr Vardaman’s ideas very seriously.

Jerry Vardaman’s claims

Although Jerry Vardaman never published any peer-reviewed papers on his discovery, his paper “Jesus’ Life, A New Chronology” in Chronos, Kairos, Christos I (Eisenbrauns, 1989) introduced the concept of microletters:

These discoveries resulted from research done in the coin room of the British Museum in the summer of 1984, when Nikos Kokkinos was working with me. Since Kokkinos and I have not formally discussed the following conclusions, I alone must be held accountable for them, even though we do agree on at least two basic points: the existence of microletters on ancient coins and the date of Jesus’ birth… On both subjects I present evidence found on coins of the period, coins that are literally covered with microletters.

Apart from this chapter in a relatively

obscure publication on biblical chronology, there are no formally

published reports of the discovery. A series of three lectures,

delivered to the Hong Kong Baptist Theological Seminary in 1998 has been

in circulation for some time; they can be downloaded here as poor

quality pdfs 1, 2 and 3.

That is the total of Vardaman’s output on the subject of microletters,

although it should be noted that he also claimed to identify them on

stone-cut inscriptions.

The academic response was almost

non-existent. There were no (reported) attempts by others to validate

Vardaman’s alleged discovery, no critiques of his technique and, most

worryingly, no public statement on the matter by Nikos Kokkinos,

alleged to have been the co-discoverer of microletters. Nikos Kokkinos

is well known as an expert on ancient coinage and on the coinage of the

Herodian dynasty in particular, but he seems never to have published

anything claiming to have detected microletters on the objects he

studies. He is someone who is unafraid of courting controversy (he was

one of the co-authors of Centuries of Darkness,

a radical attempt to revise the chronology of the ancient Near East and

Aegean that has not met with the approval of the majority of scholars),

so this failure to mention them is very surprising. The only response

seems to have been a review, “Theory of Secret Inscriptions on Coins is

Disputed”, by the prominent numismatist David Hendin in The Celator

(Volume 5 no 3 (March 1991), 28-32). The magazine published a rebuttal

to Hendin’s criticisms by Jerry Vardaman, which added no new evidence to

his published work.

Critique of the “microletters”

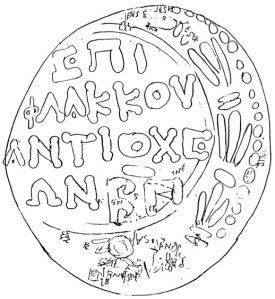

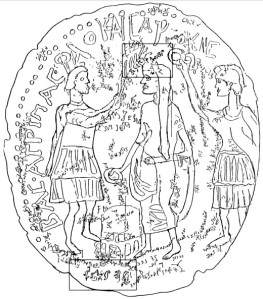

Another example of microletters, after Vardaman’s “Jesus’ Life, A New Chronology” Figure 2 (reverse)

The lack of acknowledgement by the wider

academic community is not necessarily a result of a general

unwillingness to look at Jerry Vardaman’s ideas, nor is it the closing

of ranks against novel hypotheses (a claim that many “alternative”

archaeologists make to explain why mainstream archaeologists tend to

ignore their works). It is a direct result of Vardaman’s failure to

publish his results adequately by submitting them to peer-reviewed

publications. It is also because of the audience to which he pitched his

ideas: instead of presenting them to numismatists and epigraphers, who

would be those best placed to evaluate them, he concentrated on the

religious studies audience, particularly those of a biblical literalist

bent. In some ways, this is not surprising (Vardaman was an ordained

Baptist minister), but it is worrying.

One possibility for the lack of wider

discussion of “microletters” is that other archaeologists simply did not

believe that they exist. There are enormous problems with them, of

course. Although Vardaman does not supply scales to his drawings of the

coins, the letters he claims to have detected are tiny, less than half a

millimetre in height. They could only have been added to the coin dies

using a very fine, hard-tipped scriber of some kind, although he

produced no archaeological evidence for this type of tool. We must also

ask ourselves why an ancient coin die-maker would have added words and

phrases that would have been invisible to the coin users. And why did he

use a mixture of Greek and Latin on coins that have regular

inscriptions only in Greek? How have letters so small survived the

day-to-day wear to which all coins are subject so that Vardaman could

discover them? How are they visible beneath the patina that develops on

all archaeologically recovered coins? If corrosion products have been

removed or stabilised, how have the microletters survived the cleaning

process? These are insurmountable difficulties and Vardaman was never

questioned about them.

There is a more serious problem, though.

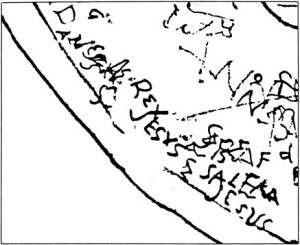

As well as the promiscuous mixing of Greek and Latin words in the

microletter inscriptions, there is at least one instance published by

Vardaman of the letter J, used in the name Jesus. This letter simply did

not exist in either the Greek or Latin alphabets of the time of Jesus:

it was invented by the Italian humanist Gian Giorgio Trissino

(1478–1550) to represent a sound for which the existing Latin alphabet

of Early Modern period had no character. It was based on the final -i in

Roman numerals in medieval manuscript traditions, where ii, iii, vii

and viii were conventionally written ij, iij, vij, viij, a purely

decorative feature. It can not have been “microinscribed” on a coin of

the first century CE.

Explaining non-existent “microletters”

So what are we to make of Vardaman’s

hypothesis? Well, it’s bunk, pure and simple. It is Bad Archaeology of a

very obvious kind: Jerry Vardaman was seeing things that just don’t

exist. We have to ask ourselves why he did so. He does not seem to have

set out to hoax people and seems genuinely to have believed in the

existence of microletters. The well known atheist historian Richard Carrier has suggested that in later life, Vardaman was suffering from a “chronic mental illness”.

This may be going too far. Jerry Vardaman was certainly deluded about

the existence of his microletters and continued to assert that he was

correct, without bringing forward any evidence, until the end of his

life. I suspect that his religious convictions had a part to play in his

insistence on their reality.

As a Baptist of decidedly literalist

leanings, Jerry Vardaman regarded scripture as infallible; the well

known problem of the impossible date for the birth of Jesus given in the

Gospel of Luke, who appears to date it to 6 CE during the governorship

of Quirinus in Syria, has led to a variety of ingenious explanations.

Vardaman was of the view that there were two governors of Syria named

Quirinus: the one mentioned by Josephus and well known to history and an

earlier, more shadowy figure, who was governor in 12 BCE, the date

Vardaman preferred for the birth of Jesus. His microletters formed a

major element in his identification of the supposedly early Quirinius

(as did microletters on stone inscriptions), who is otherwise unknown.

Vardaman’s desperation to confirm the account of Luke in the face of the

enormous difficulty posed by the implied date of the census that would

have brought Joseph and Mary to Bethlehem led him into serious errors of

judgement: he literally saw what he wanted.